S

|

In this section, we will discuss the results of the constrained

molecular dynamics simulations performed to study the CH![]() Cl +

Cl

Cl +

Cl![]() reaction in a dilute aqueous solution of HCl. To obtain the

free energy barrier

reaction in a dilute aqueous solution of HCl. To obtain the

free energy barrier ![]() , we calculated the mean force of constraint

, we calculated the mean force of constraint

![]() at 5 points (

at 5 points (

![]() )

along the reaction coordinate

)

along the reaction coordinate ![]() (Eqn. 2). As a

verification of the simulations,

(Eqn. 2). As a

verification of the simulations,

![]() was also calculated at three points at the product

side of the reaction coordinate (

was also calculated at three points at the product

side of the reaction coordinate (

![]() ). Subsequently, two extra simulations were performed

for the points

). Subsequently, two extra simulations were performed

for the points ![]() (because at

(because at ![]() there was still

too large an attraction between CH

there was still

too large an attraction between CH![]() Cl and Cl

Cl and Cl![]() , whereas for the

separated reactants, the interaction between the reactants is expected

approach to zero

, whereas for the

separated reactants, the interaction between the reactants is expected

approach to zero![]() and at

and at ![]() (where we expected an extremum in

(where we expected an extremum in

![]() , after having fitted the

first five points).

, after having fitted the

first five points).

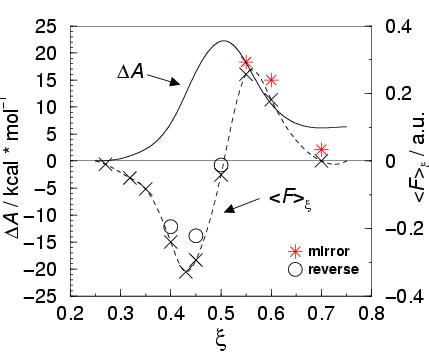

The results for the mean force of constraint are plotted in figure 3.5

(and listed in table 3.8).

The dashed line is a cubic spline fitted to

the calculated points. Integration of the mean force of constraint

with respect to ![]() (according to equation 3.7)

results in the free energy barrier, shown by the solid line in the

figure, yielding a barrier height of 22.2 kcal/mol. Taking into

account the 8 kcal/mol error in the gas phase reaction, the free

energy barrier of the reaction in aqueous solution would be

30.2 kcal/mol; an overestimation of about 3.6 kcal/mol compared to the

experimental result of 26.6 kcal/mol [66].

(according to equation 3.7)

results in the free energy barrier, shown by the solid line in the

figure, yielding a barrier height of 22.2 kcal/mol. Taking into

account the 8 kcal/mol error in the gas phase reaction, the free

energy barrier of the reaction in aqueous solution would be

30.2 kcal/mol; an overestimation of about 3.6 kcal/mol compared to the

experimental result of 26.6 kcal/mol [66].

Because of the symmetry of the reaction the calculated energy profile

should be symmetric. From the figure, it is obvious that the shape has

a significant asymmetry.

This asymmetry has been illustrated by asterisks in the figure. They

have been drawn in figure 3.5 above the three

points at the product side of the reaction (

![]() ) to picture the equivalent points at the reactant side (with

the negative force) for comparison. Moreover, the mean force of

constraint does not vanish at the transition state

) to picture the equivalent points at the reactant side (with

the negative force) for comparison. Moreover, the mean force of

constraint does not vanish at the transition state ![]() as it

should. The three product-side points as well as the point at the

transition state apply to

as it

should. The three product-side points as well as the point at the

transition state apply to

![]() configurations with a driving force

that is smaller toward the product-side (or larger toward the

reactant-side) than was expected from the other points at the

reactant-side. This can be characterized as hysteresis when forcing

the reaction by the method of constraint. Most likely, this hysteresis

is due to the surrounding water shell, which apparently adapts too

slowly to the changing reactants configuration, when going from one

simulation to the next by increasing

configurations with a driving force

that is smaller toward the product-side (or larger toward the

reactant-side) than was expected from the other points at the

reactant-side. This can be characterized as hysteresis when forcing

the reaction by the method of constraint. Most likely, this hysteresis

is due to the surrounding water shell, which apparently adapts too

slowly to the changing reactants configuration, when going from one

simulation to the next by increasing ![]() .

.

To test this explanation, we performed calculations

for the reversing of the reaction.

We performed the backward reaction for three points (

![]() ), where we started from the constrained MD run at

), where we started from the constrained MD run at

![]() and moved the constraint value slowly to the previous point

on the reaction coordinate. Subsequently, we equilibrated for 2.5 ps,

collected the force of constraint for 3 ps, and moved on to the next

point, similar to the points of the forward reaction direction. The

results are shown by the circles in figure 3.5.

The hysteresis at the first point,

and moved the constraint value slowly to the previous point

on the reaction coordinate. Subsequently, we equilibrated for 2.5 ps,

collected the force of constraint for 3 ps, and moved on to the next

point, similar to the points of the forward reaction direction. The

results are shown by the circles in figure 3.5.

The hysteresis at the first point, ![]() , has disappeared since

, has disappeared since

![]() is zero (within the error in the force), as expected.

Apparently, the solvent configuration is not pulling on either side

of the reacting complex, at this point.

For the other two points, we now find smaller absolute values for the

mean force of constraint than we found in the forward reaction. This

is consistent with the picture of a ``memory effect'' in the solvent,

i.e. a too slow adaptation of the water configuration to the changed

reaction coordinate.

is zero (within the error in the force), as expected.

Apparently, the solvent configuration is not pulling on either side

of the reacting complex, at this point.

For the other two points, we now find smaller absolute values for the

mean force of constraint than we found in the forward reaction. This

is consistent with the picture of a ``memory effect'' in the solvent,

i.e. a too slow adaptation of the water configuration to the changed

reaction coordinate.

A rough estimate of the systematic error on the free energy barrier

due to the hysteresis can be made, by assuming that the deviation in

the force will increase linearly

from zero at the starting point of the separate reactants (

![]() )

to the observed -0.041 a.u.

at the transition state. Correcting the free energy profile for the corresponding

overestimation (3.2 kcal/mol), gives a barrier height of 27 kcal/mol.

The excellent agreement with experiment (26.6 kcal/mol), after the corrections

for the DFT-GGA error in the gas phase transition state energy and the hysteresis

in the constrained MD runs, must be a bit fortuitous, for the following

reasons. First of all we have found the accuracy of the DFT-BP description

of the energetics of the solvation to be of the order of 1 kcal/mol.

Secondly, the experimental result refers to more dilute

solution at neutral pH, with typically potassium used for the counter cation.

In the present calculation, a proton acted as counter-cation, which

can be expected to have some influence on the energetics of the reaction via

its charge and solvation structure.

)

to the observed -0.041 a.u.

at the transition state. Correcting the free energy profile for the corresponding

overestimation (3.2 kcal/mol), gives a barrier height of 27 kcal/mol.

The excellent agreement with experiment (26.6 kcal/mol), after the corrections

for the DFT-GGA error in the gas phase transition state energy and the hysteresis

in the constrained MD runs, must be a bit fortuitous, for the following

reasons. First of all we have found the accuracy of the DFT-BP description

of the energetics of the solvation to be of the order of 1 kcal/mol.

Secondly, the experimental result refers to more dilute

solution at neutral pH, with typically potassium used for the counter cation.

In the present calculation, a proton acted as counter-cation, which

can be expected to have some influence on the energetics of the reaction via

its charge and solvation structure.

|

|

||||

| Attacking chloride | Leaving chloride | |||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| 0.27 | 5.4 | 6.3 | - | - |

|

|

||||

| 0.32 | 4.3 | 5.1 | - | - |

|

|

||||

| 0.35 | 4.9 | 4.6 | - | - |

|

|

||||

| 0.40 | 4.7 | 4.4 | - | - |

|

|

||||

| 0.43 | 4.8 | 4.8 | - | - |

|

|

||||

| 0.45 | 4.2 | 4.5 | 1.1 | 4.4 |

|

|

||||

| 0.50 | 3.3 | 4.3 | 2.7 | (4.8) |

|

|

||||

| 0.50 |

2.9 | (5.6) | 3.0 | (4.3) |

|

|

||||

| 0.55 | 2.2 | (4.8) | 4.0 | 5.0 |

|

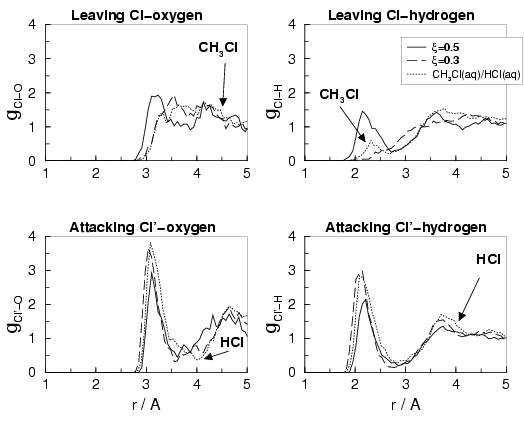

To start with the separated reactants at ![]() , we note that

the distribution functions

, we note that

the distribution functions

![]() and

and

![]() of the attacking

chloride anion (dashed lines in the lower graphs) are

very similar to the functions of pure HCl in water (dotted lines; see also

figure 3.3). The distribution around the leaving chloride

atom at

of the attacking

chloride anion (dashed lines in the lower graphs) are

very similar to the functions of pure HCl in water (dotted lines; see also

figure 3.3). The distribution around the leaving chloride

atom at ![]() (upper two graphs) is in agreement with pure CH

(upper two graphs) is in agreement with pure CH![]() Cl

in water (dotted lines), except for a small peak in

Cl

in water (dotted lines), except for a small peak in

![]() at

at ![]() Å in the latter. The small peak in the pure CH

Å in the latter. The small peak in the pure CH![]() Cl solution

(case b) in section 3.2.4) can be attributed

to one water molecule which is hydrogen bonded to the Cl of methylchloride.

The main reason for the absence of this peak in

Cl solution

(case b) in section 3.2.4) can be attributed

to one water molecule which is hydrogen bonded to the Cl of methylchloride.

The main reason for the absence of this peak in

![]() of the

leaving Cl, must be the presence of the Cl

of the

leaving Cl, must be the presence of the Cl![]() anion, which has a strong

influence on the solvent structure.

The coordination numbers (in table 3.7) shows that

the attacking chloride anion is solvated by about five water molecules, whereas

the separate CH

anion, which has a strong

influence on the solvent structure.

The coordination numbers (in table 3.7) shows that

the attacking chloride anion is solvated by about five water molecules, whereas

the separate CH![]() Cl does not show any attraction of water atoms. Note

that

Cl does not show any attraction of water atoms. Note

that

![]() confirms that this starting

constrained simulation indeed does not fully resemble separated reactants

as concluded in section 3.3.4,

whereas the extra simulation of

confirms that this starting

constrained simulation indeed does not fully resemble separated reactants

as concluded in section 3.3.4,

whereas the extra simulation of ![]() shows coordination numbers of

5.4 and 6.3 in agreement with the values for the pure HCl in water (5.2 and

6.5, table 3.5).

shows coordination numbers of

5.4 and 6.3 in agreement with the values for the pure HCl in water (5.2 and

6.5, table 3.5).

Next, we discuss the radial distribution functions for the transition state

configurations (solid lines).

These show a more equal solvation of the attacking and

leaving chloride ions. However, the first peaks of the

attacking chloride ion are still much more pronounced than the peaks

arising from the first solvation shell around the leaving

chloride. Also, the minimum at ![]() Å is much deeper in

Å is much deeper in

![]() than in

than in

![]() . This asymmetry in

the chloride solvation is reflected less strongly in the coordination

numbers (table 3.7).

The attacking chloride still has on average 3.3 hydrogens in

the first shell, while the leaving chloride has only 2.7.

The Cl-O coordination numbers cannot be determined accurately because

the oxygen distribution function

. This asymmetry in

the chloride solvation is reflected less strongly in the coordination

numbers (table 3.7).

The attacking chloride still has on average 3.3 hydrogens in

the first shell, while the leaving chloride has only 2.7.

The Cl-O coordination numbers cannot be determined accurately because

the oxygen distribution function

![]() of the leaving Cl

does not show an unambiguous minimum. Still, from the hydrogen distribution,

we can conclude that the attacking Cl is stronger solvated than the leaving

Cl, at

of the leaving Cl

does not show an unambiguous minimum. Still, from the hydrogen distribution,

we can conclude that the attacking Cl is stronger solvated than the leaving

Cl, at ![]() , which must be the grounds for the effective force of

constraint at the transition state.

Indeed, in the reversed reaction direction, where we found the expected

, which must be the grounds for the effective force of

constraint at the transition state.

Indeed, in the reversed reaction direction, where we found the expected

![]() , we also see a more symmetric

hydrogen distribution (radial distribution functions not shown)

and coordination number: 2.9 for the attacking Cl and 3.0 for the leaving Cl.

Just before the transition state, the leaving chloride has only one hydrogen in the

``first shell'' (

, we also see a more symmetric

hydrogen distribution (radial distribution functions not shown)

and coordination number: 2.9 for the attacking Cl and 3.0 for the leaving Cl.

Just before the transition state, the leaving chloride has only one hydrogen in the

``first shell'' (

![]() ), whereas just

after the transition state the attacking chloride still has two

hydrogens (

), whereas just

after the transition state the attacking chloride still has two

hydrogens (

![]() ). This difference

leads to a larger value for the mean force of constraint at

). This difference

leads to a larger value for the mean force of constraint at ![]() in comparison with

in comparison with ![]() , and gives a structural explanation for

the observed hysteresis in the free energy profile of

figure 3.5.

, and gives a structural explanation for

the observed hysteresis in the free energy profile of

figure 3.5.