The pathway relaxation from an artificially constructed reaction pathway

to a pathway without the memory of the initial construction, was obtained

in two steps (for both sequences A and B).

The first step took place in the first pathway generation,

namely by taking completely random atomic momenta at

the starting point (which was the transition state configuration of

the initial reaction pathway). The second part of the relaxation consisted

of nine more sequential pathway generations, in which we observed

(a) increasingly faster terminations of the leaving OH. radical

due to shorter lifetimes

![]() and

(b) a shift from the direct rebound mechanism and the long-wire

two-step mechanism to the short-wire two-step mechanism.

and

(b) a shift from the direct rebound mechanism and the long-wire

two-step mechanism to the short-wire two-step mechanism.

|

These changes along the two sequences of pathways can be

understood as the result of the relaxation of the solvent environment

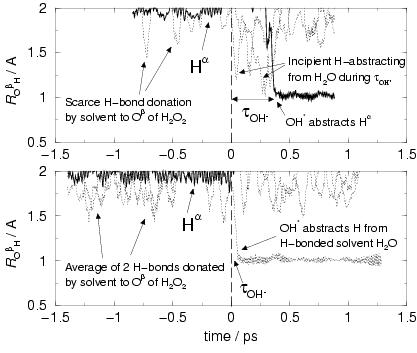

of the reactants. As an illustration, figure 7.6

shows the hydrogen-oxygen distances

![]() as a function

of time for the solvent water hydrogens within a radius of 2 Å

of the H

as a function

of time for the solvent water hydrogens within a radius of 2 Å

of the H![]() O

O![]() oxygen, O

oxygen, O![]() , for the initial unrelaxed

reaction pathway (upper graph) and the last pathway (no. 10) of sequence A

(lower graph). The moment that the hydrogen peroxide O-O distance

equaled

, for the initial unrelaxed

reaction pathway (upper graph) and the last pathway (no. 10) of sequence A

(lower graph). The moment that the hydrogen peroxide O-O distance

equaled

![]() Å, which marks the moment of coordination

and dissociation of the hydrogen peroxide to the iron complex,

was taken for time

Å, which marks the moment of coordination

and dissociation of the hydrogen peroxide to the iron complex,

was taken for time ![]() , marked by the vertical dashed line.

Before

, marked by the vertical dashed line.

Before ![]() , we see the lines arising from the hydrogen bonded

solvent water molecules to the yet intact hydrogen peroxide and

from the H

, we see the lines arising from the hydrogen bonded

solvent water molecules to the yet intact hydrogen peroxide and

from the H![]() O

O![]() hydrogen H

hydrogen H![]() (distinguished by the bold

line in the graphs). The

(distinguished by the bold

line in the graphs). The

![]() distance,

fluctuating around 1 Å has been left out for clarity. After

distance,

fluctuating around 1 Å has been left out for clarity. After

![]() , we see the lines arising from the hydrogen bonded

solvent water molecules to the, at first, leaving OH. radical

and later formed water molecule oxygen. Note that the change from

OH. radical into water molecule occurs almost 300 fs later

in the initial pathway compared to the relaxed pathway and that the

OH. abstracts H

, we see the lines arising from the hydrogen bonded

solvent water molecules to the, at first, leaving OH. radical

and later formed water molecule oxygen. Note that the change from

OH. radical into water molecule occurs almost 300 fs later

in the initial pathway compared to the relaxed pathway and that the

OH. abstracts H![]() (from the formed Fe

(from the formed Fe![]() -OH

-OH![]() )

in the initial pathway but in the relaxed pathway it abstracts

the hydrogen from one of the hydrogen bonded solvent molecules.

Also, we see in the upper graph of the unrelaxed pathway jumps

from two solvent hydrogens to the OH. radical between

)

in the initial pathway but in the relaxed pathway it abstracts

the hydrogen from one of the hydrogen bonded solvent molecules.

Also, we see in the upper graph of the unrelaxed pathway jumps

from two solvent hydrogens to the OH. radical between ![]() ps,

which however do not make it to a H atom at the water molecule

that is formed; this is ``achieved'' by the H

ps,

which however do not make it to a H atom at the water molecule

that is formed; this is ``achieved'' by the H![]() .

.

The initial reaction pathway was constructed by driving hydrogen

peroxide out of the coordination shell from the

[Fe![]() (H

(H![]() O)

O)![]() (H

(H![]() O

O![]() )]

)]![]() complex, as shown

earlier in figure 7.1 between

complex, as shown

earlier in figure 7.1 between ![]() ps. We thus

started from H

ps. We thus

started from H![]() O

O![]() , separated from the complex, that could

hardly have formed a relaxed solvation shell, which however is expected

to exist for separated reactants in the reactant well. This is seen in the

upper graph of figure 7.6 from the absence of

hydrogen bonds from solvent waters before

, separated from the complex, that could

hardly have formed a relaxed solvation shell, which however is expected

to exist for separated reactants in the reactant well. This is seen in the

upper graph of figure 7.6 from the absence of

hydrogen bonds from solvent waters before ![]() . The lower

graph, of reaction pathway no. 10, on the other hand,

shows two solvent hydrogens with

. The lower

graph, of reaction pathway no. 10, on the other hand,

shows two solvent hydrogens with

![]() distances between

1.5-2.0 Å[216], indicating the adoption of

hydrogen bonds from the solvent network and thus indicating that

relaxation of the solvent structure has occurred around hydrogen peroxide.

Because hydrogen peroxide takes part in the three-dimensional solvent

network via the formed hydrogen bonds between solvent molecules and

H

distances between

1.5-2.0 Å[216], indicating the adoption of

hydrogen bonds from the solvent network and thus indicating that

relaxation of the solvent structure has occurred around hydrogen peroxide.

Because hydrogen peroxide takes part in the three-dimensional solvent

network via the formed hydrogen bonds between solvent molecules and

H![]() O

O![]() before the reaction with iron (which is also illustrated in the

first snapshots in figure 7.5)

the leaving OH. radical can terminate much faster via H-bond

wires in the network, resulting in the lower

lifetime

before the reaction with iron (which is also illustrated in the

first snapshots in figure 7.5)

the leaving OH. radical can terminate much faster via H-bond

wires in the network, resulting in the lower

lifetime

![]() .

.

Have we now found the most likely mechanism for the iron(II) catalyzed

dissociation of hydrogen peroxide? Let us first consider the

alternative to the proposed two-step mechanism, namely

the rebound mechanism.

Of course, whether the two-step mechanism is indeed more

favorable than this alternative can in principle only be

established after generating a very large number of independent

reaction pathways, and compare the probabilities of the

two mechanisms. Our transition path sampling sequences indicate

the rebound mechanism to have lower probability than the two-step

mechanism. This can be rationalized from the following motive. In

the rebound mechanism, the leaving OH. has to abstract the

Fe![]() -OH

-OH![]() hydrogen. From our results, however,

we see that the leaving OH. from the solvated hydrogen

peroxide will jump rapidly along an H-bond wire to termination,

which is much more probable, simply because the

Fe

hydrogen. From our results, however,

we see that the leaving OH. from the solvated hydrogen

peroxide will jump rapidly along an H-bond wire to termination,

which is much more probable, simply because the

Fe![]() -OH

-OH![]() hydrogen is further away

after the O-O lysis than the solvent molecules forming H-bonds.

hydrogen is further away

after the O-O lysis than the solvent molecules forming H-bonds.

The alternative mechanism to the two aforementioned ones (with a ferryl ion as the active intermediate) is Haber and Weiss' free radical mechanism. We have given arguments in references bernd3, bernd4 and franco1 why we believe this mechanism to be unlikely. If we would still want to compare its probability to that of the two-step (ferryl ion producing) mechanism, we should consider that for the Haber and Weiss radical mechanism, the leaving OH. radical has to become a ``free radical'' by jumping along an H-bond wire of a number of solvent waters. The OH. then should become disconnected, possibly by a thermal rotation of one of the involved solvent waters, so that the OH. radical cannot jump back to terminate at the aquairon complex. In our rather small system, the occurrence or non-occurrence of the latter event cannot be adequately tested since an OH. radical that leaves the complex to become a free radical via a short wire of, say, three solvent waters, is already too close to the periodic image of the iron complex at which it can terminate. For reaction path sampling of the Haber and Weiss free radical mechanism, a larger unit cell would be essential.

Let us finally note that the AIMD simulations are not without shortcomings. The box size was chosen rather small in order to make the computations feasible. The OH. radical could therefore jump via a hydrogen bonded wire of three water molecules through the unit cell to a neighboring periodic copy of the cell. So, although the reactants have at least one complete hydration shell, and the major solvation contributions are included in the calculations, the long range effects are approximated and the simulations can, in the future when computers become faster, be improved by increasing the box size and the number of solvent molecules in the box. Other (minor) error sources are the neglect of pressure effects in the NVT ensemble, the classical treatment of the nuclear dynamics neglecting tunneling and zero point energy effects, and the accuracy of electronic structure method which is with the present exchange-correlation functions of DFT about 1 kcal/mol, and significantly larger (due to approximations in the PAW method) when changes in oxidation state of the metal are involved, see section 7.3.