In this section, new reactive pathways for the O-O bond breaking upon

coordination of an hydrogen

peroxide molecule to an iron(II) ion in aqueous solution will be

generated, using the transition path sampling technique. To this end,

a point on an existing reaction pathway has to be chosen as the starting

configuration of a new pathway. In the present sampling procedure, a configuration

file with the atomic configurations and wavefunction coefficients was saved

every 1000 time steps (145 femtoseconds). One of the saved

configurations was randomly chosen as the starting point for a new

pathway. The first new successful reaction path initiated from a point on our

initial pathway, will be referred to as the first generation path;

a successful reaction path initiated from a point on this first

generation path makes than a second generation path, etcetera.

A sequence of reactive pathways is a series of subsequent

generations.

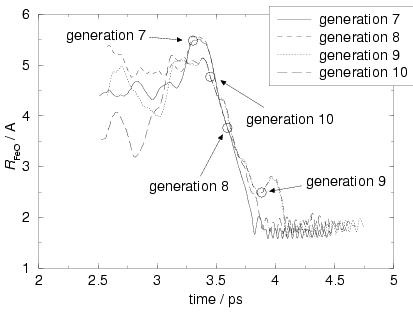

Figure 7.4 illustrates the procedure for four pathways;

the circles denote the chosen starting points where on each ![]() generation path a new

generation path a new

![]() generation path branches off.

On a certain pathway, the time

between its own starting point and the starting point of the next

pathway, varied between 0.29 and 0.58 picoseconds, which is

in a sense the time that the system is allowed to relax on a pathway before

a next generation one branches off.

generation path branches off.

On a certain pathway, the time

between its own starting point and the starting point of the next

pathway, varied between 0.29 and 0.58 picoseconds, which is

in a sense the time that the system is allowed to relax on a pathway before

a next generation one branches off.

|

We calculated two sequences (sequence A and sequence B),

each with a length of 10 generations. For the first generation of each sequence

we took one of the 20 trajectories calculated earlier to verify the transition

state location on the initial reaction pathway, shown in the right-hand-side

plots of figure 7.3. That is, the first generation

pathways for both sequences A and B branch off at the transition state

point of our initial pathway, with random atomic momenta drawn from a

![]() K Boltzmann distribution. Of course, figure 7.3

shows only halves of reactive pathways (namely from the TS point to

either the product state or the reactant state), so the other half was

calculated, for our two first generations, by integrating the equations of

motion backwards in time from the starting configuration of the

reactive pathway (i.e. the TS point).

K Boltzmann distribution. Of course, figure 7.3

shows only halves of reactive pathways (namely from the TS point to

either the product state or the reactant state), so the other half was

calculated, for our two first generations, by integrating the equations of

motion backwards in time from the starting configuration of the

reactive pathway (i.e. the TS point).

In table 7.2, which shows some characteristics

of the computed pathways for sequence A (first 11 rows) and sequence B

(last 9 rows), we see that the first generation pathways of sequences

A and B are quite different from each other. For sequence A, the pathway

does not show the direct mechanism of our initial pathway in which the

ferryl ion (Fe![]() O

O![]() ) is formed via a rebound of the leaving

OH. radical, which abstracts the hydrogen of the intermediate

Fe

) is formed via a rebound of the leaving

OH. radical, which abstracts the hydrogen of the intermediate

Fe![]() -OH. Instead, the leaving OH. radical jumps after

a lifetime of

-OH. Instead, the leaving OH. radical jumps after

a lifetime of

![]() fs via two solvent water

molecules and terminates at a water ligand of a periodic image of the

iron complex in a neighboring copy of the unit cell to form the dihydroxo

iron(IV) moiety. This is indeed the first step of the two-step mechanism that we

have seen before

in simulations starting from hydrogen peroxide already coordinated to

pentaaquairon(II).[171,146] In a second step (see last

column in table 7.2), the ferryl

ion was formed by donation of a proton by one of the hydroxo ligands to

the solvent. For sequence B, the first generation pathway shows the rebound

mechanism, although also an incipient OH. radical shunt via two solvent

water molecules is observed, but this OH.-shunt is not completed,

the motion of the solvent hydrogens is reversed when the Fe

fs via two solvent water

molecules and terminates at a water ligand of a periodic image of the

iron complex in a neighboring copy of the unit cell to form the dihydroxo

iron(IV) moiety. This is indeed the first step of the two-step mechanism that we

have seen before

in simulations starting from hydrogen peroxide already coordinated to

pentaaquairon(II).[171,146] In a second step (see last

column in table 7.2), the ferryl

ion was formed by donation of a proton by one of the hydroxo ligands to

the solvent. For sequence B, the first generation pathway shows the rebound

mechanism, although also an incipient OH. radical shunt via two solvent

water molecules is observed, but this OH.-shunt is not completed,

the motion of the solvent hydrogens is reversed when the Fe![]() -OH

intermediate donates its hydrogen to the leaving OH. radical.

-OH

intermediate donates its hydrogen to the leaving OH. radical.

From these two first generation pathways, we successively generated

new pathways by taking a configuration from a path and changing the

atomic momenta. The momenta were changed by randomly drawing new

momenta from a gaussian distribution of ![]() K or

K or ![]() K and adding these

to the old momenta (and correcting for any total momentum of the system).

The success rate of obtaining a new pathway connecting reactants and

products was about 50%. In both sequences, accidentally,

the fifth generation

pathway was started from an unsuccessful fourth generation

pathway that started in the product well and recrossed back to

the product well, although the iron-oxygen distances reached a

separation of more than 4 Å (which is our order parameter defining the

reactant well) in both fourth generation pathways.

K and adding these

to the old momenta (and correcting for any total momentum of the system).

The success rate of obtaining a new pathway connecting reactants and

products was about 50%. In both sequences, accidentally,

the fifth generation

pathway was started from an unsuccessful fourth generation

pathway that started in the product well and recrossed back to

the product well, although the iron-oxygen distances reached a

separation of more than 4 Å (which is our order parameter defining the

reactant well) in both fourth generation pathways.

|

|

|||||

| generation | mechanism |

|

# H |

terminating | final obs. |

| H-bond wire | Fe complex | species | |||

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

| Relaxation sequence A | |||||

| 1 | long wire | 149 | 2 | copy | ferryl |

| 2 | long wire | 380 | 2 | copy | ferryl |

| 3 | short wire | 322 | 0 | same | ferryl |

| 5 |

long wire | 289 | 2 | copy | Fe |

| 6 | long wire | 265 | 2 | copy | Fe |

| 7 | long wire | 150 | 3 | copy | ferryl |

| 7 | short wire | 70 | 1 | same | ferryl |

| 8 | short wire | 73 | 1 | same | Fe |

| 9 | short wire | 70 | 1 | same | Fe |

| 9 | short wire | 65 | 1 | same | Fe |

| 10 | short wire | 66 | 1 | same | Fe |

| generation | mechanism |

|

# H |

terminating | final obs. |

| H-bond wire | Fe complex | species | |||

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

| Relaxation sequence B | |||||

| 1 |

both | 101 | 2 | both | ferryl |

| 2 | direct | 121 | 0 | same | ferryl |

| 3 | direct | 133 | 0 | same | ferryl |

| 5 |

direct | 251 | 0 | same | ferryl |

| 6 | direct | 248 | 0 | same | ferryl |

| 7 | direct | 141 | 0 | same | ferryl |

| 8 | long wire | 43 | 2 | copy | Fe |

| 9 | long wire | 42 | 2 | copy | Fe |

| 10 | short wire | 93 | 1 | same | Fe |

Taking a closer look at table 7.2, we see trends along

the two sequences which could indicate that indeed our initial pathway

is an atypical one and relaxation towards more representative pathways

does take place. For example, the time that

the leaving OH. radical remains intact before abstracting a hydrogen

from the complex or a solvent water (the lifetime

![]() , which is measured from the moment of O-O

lysis, defined as

, which is measured from the moment of O-O

lysis, defined as

![]() Å, until the first H-abstraction

by OH.),

is seen to decrease in both sequences. Secondly, in both sequences

the followed mechanisms change via or from the ``long-wire two-step''

mechanism (in which the OH. radical in the first step terminates via a wire of

two or three solvent waters at a water ligand of the periodic image

of the complex) to the ``short-wire two step'' mechanism. In the

latter case, the leaving OH. radical terminates in the first step at an adjacent

water ligand (thus stays in the same unit cell) via one bridging

solvent molecule, forming the dihydroxo iron(IV) complex.

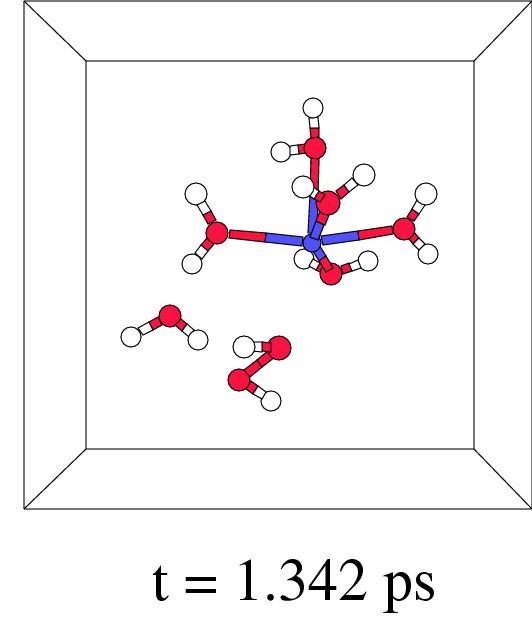

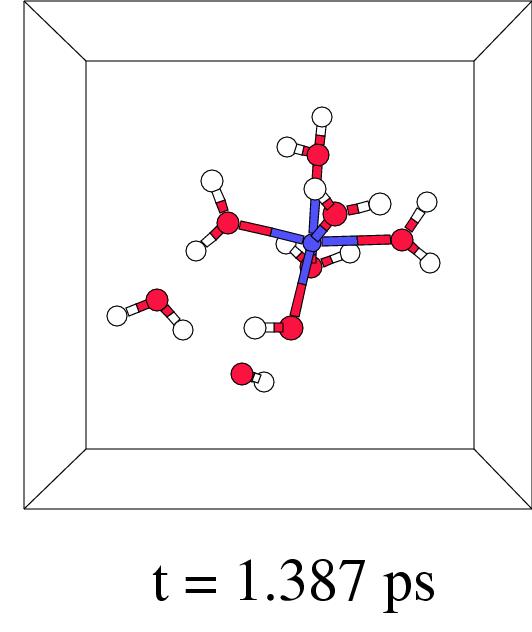

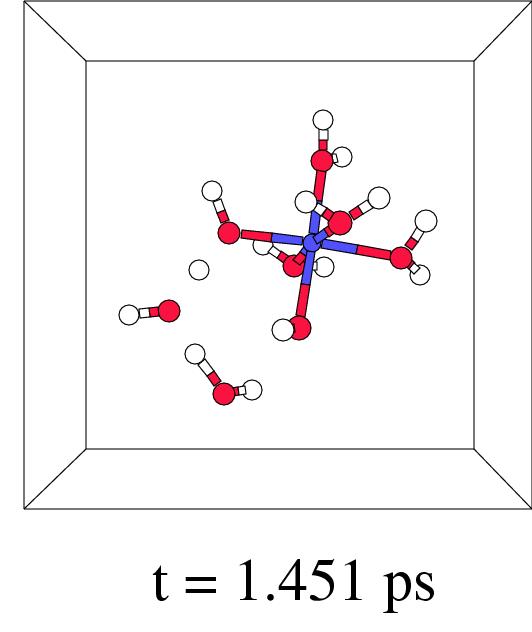

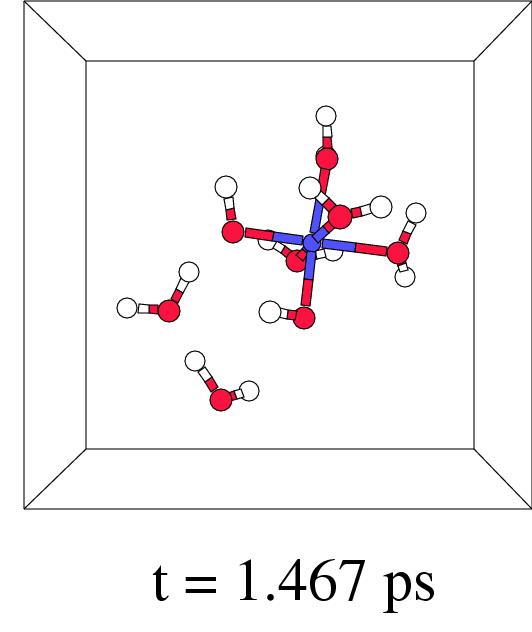

Figure 7.5 shows in four snapshots the H

Å, until the first H-abstraction

by OH.),

is seen to decrease in both sequences. Secondly, in both sequences

the followed mechanisms change via or from the ``long-wire two-step''

mechanism (in which the OH. radical in the first step terminates via a wire of

two or three solvent waters at a water ligand of the periodic image

of the complex) to the ``short-wire two step'' mechanism. In the

latter case, the leaving OH. radical terminates in the first step at an adjacent

water ligand (thus stays in the same unit cell) via one bridging

solvent molecule, forming the dihydroxo iron(IV) complex.

Figure 7.5 shows in four snapshots the H![]() O

O![]() coordination to iron(II), the O-O lysis, and the OH. radical

shunt and termination, of such a short-wire step. In fact,

this new ``short-wire'' reaction pathway was already predicted in

previous work where we discussed the possibilities for a radical

shunt in a very large box containing a single pentaaqua iron(II)

hydrogen peroxide complex.[171] In our present pathway

relaxation procedure it indeed appears spontaneously.

coordination to iron(II), the O-O lysis, and the OH. radical

shunt and termination, of such a short-wire step. In fact,

this new ``short-wire'' reaction pathway was already predicted in

previous work where we discussed the possibilities for a radical

shunt in a very large box containing a single pentaaqua iron(II)

hydrogen peroxide complex.[171] In our present pathway

relaxation procedure it indeed appears spontaneously.

|

The last column in table 7.2 displays the last observed

iron complex. It shows that

not always the ferryl ion is formed, but instead in many cases

an [Fe![]() (H

(H![]() O)

O)![]() (OH)

(OH)![]() ]

]![]() complex. This is

due to the dynamic equilibrium between the acidic dihydroxo species and

its conjugate base, the hydrolyzed trihydroxo species,

by proton donation to the solvent:

complex. This is

due to the dynamic equilibrium between the acidic dihydroxo species and

its conjugate base, the hydrolyzed trihydroxo species,

by proton donation to the solvent: