In the original transition path sampling procedure, to determine the

transition state of a single reaction pathway, a large number of

trajectories have to be initiated with random initial atomic velocities

from some trial point along the pathway. From the ratio of the number of

trajectories that end in the reactant well and the number of trajectories

that end in the product well, it can be determined whether

the trial point is located on the reactant side or the product side of the

TS point. If more than 50 % of the trajectories ended in the reactant well,

a new trial point is chosen located at the product side of the previous point

(and vice versa), and this procedure

is repeated until the TS point is found for which 50 % of the trajectories

generated from this point end up in the reactant well and 50 % end up in the

product well. Unfortunately, this technique is computationally

very expensive in combination with Car-Parrinello MD for our system. Therefore,

we introduce an alternative strategy to speed up the search for the TS point.

Instead of branching off many trajectories from a trial point with

random initial

atomic velocities, we start one trajectory with zero atomic velocities.

The initial direction of the system is therefore determined by the potential

energy rather than the free energy, as was the case in the original

strategy. If the system

ends up in the reactant state, we try a new trial point located more to the

products side along the pathway and vice versa. Due to the low

temperature the system will have (starting from zero Kelvin) and since

mainly the starting direction of the generated trajectory is relevant,

a damped Nosé thermostat which heats up the system to ![]() K is

used to accelerate the search even more.

Since we are however interested in the free energy transition state position,

we will in the end nevertheless use the original generation procedure

to find the exact location, but our ``zero Kelvin'' approach provides

a very cheap means to obtain a good first guess for the expensive full

procedure.

K is

used to accelerate the search even more.

Since we are however interested in the free energy transition state position,

we will in the end nevertheless use the original generation procedure

to find the exact location, but our ``zero Kelvin'' approach provides

a very cheap means to obtain a good first guess for the expensive full

procedure.

|

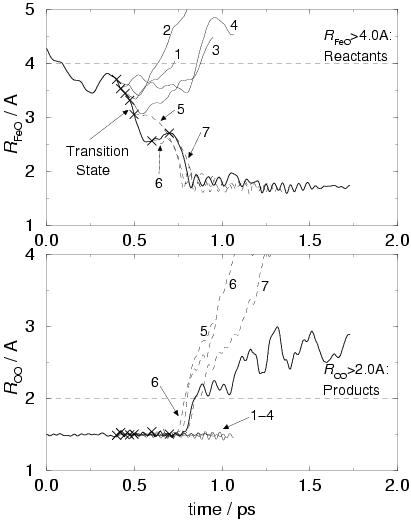

The left-hand-side graphs in figure 7.3, show the result

of our ``zero Kelvin'' approach to narrow down the TS position on our

initial pathway, defined in section 7.2, of the

reaction between pentaaqua iron(II) and hydrogen

peroxide in water. Note that the starting point of our initial path at

![]() ps in figure 7.1 has been set to

ps in figure 7.1 has been set to

![]() in figure 7.3.

The upper left-hand-side graph shows again the iron(II)

oxygen distance (bold line), which equals

in figure 7.3.

The upper left-hand-side graph shows again the iron(II)

oxygen distance (bold line), which equals

![]() Å

at the start at

Å

at the start at ![]() and decreases to

and decreases to

![]() Å 800

femtoseconds later, as hydrogen peroxide coordinates and bonds to iron

and the oxygen-oxygen bond breaks (which is shown in the lower graph).

The horizontal dashed lines depict our choice for the order parameters

that define the stable states. That is, for

Å 800

femtoseconds later, as hydrogen peroxide coordinates and bonds to iron

and the oxygen-oxygen bond breaks (which is shown in the lower graph).

The horizontal dashed lines depict our choice for the order parameters

that define the stable states. That is, for

![]() Å

the system finds itself in the reactant well of separated iron(II) and

hydrogen peroxide and for

Å

the system finds itself in the reactant well of separated iron(II) and

hydrogen peroxide and for

![]() Å the system finds

itself in the product well of dissociated hydrogen peroxide. Note that

this definition imposes no constraints--the final product may

consist of the OH. radical, a dihydroxo or oxo iron complex or

something we had not thought of yet.

Å the system finds

itself in the product well of dissociated hydrogen peroxide. Note that

this definition imposes no constraints--the final product may

consist of the OH. radical, a dihydroxo or oxo iron complex or

something we had not thought of yet.

The crosses on the bold line in both of the left-hand-side graphs denote the

trial points, from which trajectories were started with zero velocities.

We see that the trajectories originating from the first four trial points

all end up in the reactant well of

![]() Å (solid lines).

The trajectories of the next three points all end

up in the product state of

Å (solid lines).

The trajectories of the next three points all end

up in the product state of

![]() Å (dashed lines).

We have thus narrowed down the estimate for the TS location between

the fourth point at

Å (dashed lines).

We have thus narrowed down the estimate for the TS location between

the fourth point at ![]() ps (

ps (

![]() Å) and the fifth

point at

Å) and the fifth

point at ![]() ps (

ps (

![]() Å).

Å).

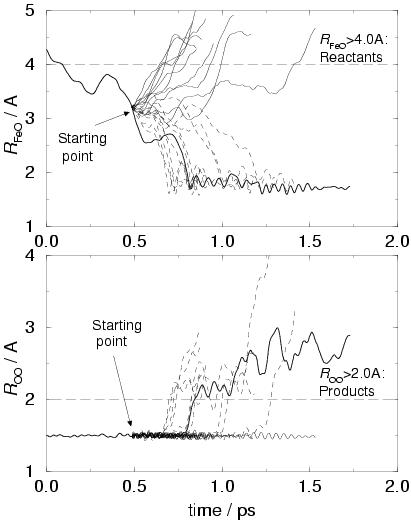

To verify this estimate of the TS location, we started 20 AIMD trajectories

at the point at ![]() ps (in the middle between point 4 and 5) where

the iron-oxygen separation is

ps (in the middle between point 4 and 5) where

the iron-oxygen separation is

![]() Å. The initial atomic

momenta were drawn from a gaussian (Boltzmann) distribution of a temperature

of

Å. The initial atomic

momenta were drawn from a gaussian (Boltzmann) distribution of a temperature

of ![]() K and corrected for any total momentum of the system.

In the right-hand-side graphs of figure 7.3, the 20

trajectories have been plotted. Ten of them end up in the reactant well

and the other ten end up in the product well. Perhaps a little fortuitously,

apparently our approach resulted in a very good estimate of the

transition state location on our reaction pathway, which could indicate

that the TS point on the free energy surface (sampled by the original

method, starting with random momenta) is not very different from the TS

point on the potential energy surface (which determines the TS position

resulting from our zero-Kelvin approach).

K and corrected for any total momentum of the system.

In the right-hand-side graphs of figure 7.3, the 20

trajectories have been plotted. Ten of them end up in the reactant well

and the other ten end up in the product well. Perhaps a little fortuitously,

apparently our approach resulted in a very good estimate of the

transition state location on our reaction pathway, which could indicate

that the TS point on the free energy surface (sampled by the original

method, starting with random momenta) is not very different from the TS

point on the potential energy surface (which determines the TS position

resulting from our zero-Kelvin approach).

The large iron-oxygen separation of

![]() Å and the

unchanged O-O distance in the transition state configuration indicates

that the barrier is mainly determined by the solvent environment for

our reaction pathway and not by the actual oxygen-oxygen lysis.

Earlier, we had inferred that this

barrier for hydrogen peroxide coordinated to iron(II) in aqueous

solution must be small in the PAW calculation as we observed the spontaneous

reaction to

the ferryl ion or to an iron(IV)dihydroxo complex, during AIMD

simulations[144,171]. Also in the present simulation the barrier for

O-O bond breaking is apparently small. It is possible that the barrier is

underestimated in the PAW calculation, in view of the overestimation of higher

oxidation states for iron as mentioned earlier in section 7.3.

In ADF calculations (STO basis functions) for the isolated complex we have

found a barrier, although a small one (6 kcal/mol), for the O-O lysis of the

coordinated hydrogen peroxide in the pentaaqua iron hydrogen peroxide complex.

The TS barrier in this case was found when the leaving O

Å and the

unchanged O-O distance in the transition state configuration indicates

that the barrier is mainly determined by the solvent environment for

our reaction pathway and not by the actual oxygen-oxygen lysis.

Earlier, we had inferred that this

barrier for hydrogen peroxide coordinated to iron(II) in aqueous

solution must be small in the PAW calculation as we observed the spontaneous

reaction to

the ferryl ion or to an iron(IV)dihydroxo complex, during AIMD

simulations[144,171]. Also in the present simulation the barrier for

O-O bond breaking is apparently small. It is possible that the barrier is

underestimated in the PAW calculation, in view of the overestimation of higher

oxidation states for iron as mentioned earlier in section 7.3.

In ADF calculations (STO basis functions) for the isolated complex we have

found a barrier, although a small one (6 kcal/mol), for the O-O lysis of the

coordinated hydrogen peroxide in the pentaaqua iron hydrogen peroxide complex.

The TS barrier in this case was found when the leaving O![]() H radical was

in the process of forming a bond to a H atom of an adjacent ligand, the calculations

in vacuo preventing it to go into solution.[145]

The TS position found in the present CPMD simulation in solution is clearly

connected to a barrier in the ligand coordination process. This can be understood

assuming that the approaching hydrogen

peroxide has to break (partially) with the energetically favorable

solvation shell before it can form an energetically favorable

bond with the iron complex. The correspondence between the methods to estimate the TS position (namely ``random momenta'' and ``zero-Kelvin'') can be understood in the same way when we also assume that the entropy loss due

to coordination is less important. For comparison, the free energy

barrier for exchange of a water molecule from the first coordination

shell of iron(II) in water was estimated to be 8.6 kcal/mol with

NMR spectroscopy, which is indeed mainly energetic (

H radical was

in the process of forming a bond to a H atom of an adjacent ligand, the calculations

in vacuo preventing it to go into solution.[145]

The TS position found in the present CPMD simulation in solution is clearly

connected to a barrier in the ligand coordination process. This can be understood

assuming that the approaching hydrogen

peroxide has to break (partially) with the energetically favorable

solvation shell before it can form an energetically favorable

bond with the iron complex. The correspondence between the methods to estimate the TS position (namely ``random momenta'' and ``zero-Kelvin'') can be understood in the same way when we also assume that the entropy loss due

to coordination is less important. For comparison, the free energy

barrier for exchange of a water molecule from the first coordination

shell of iron(II) in water was estimated to be 8.6 kcal/mol with

NMR spectroscopy, which is indeed mainly energetic (

![]() kcal/mol,

kcal/mol,

![]() kcal/mol)[215].

kcal/mol)[215].