One of the proposed second reaction steps in the oxidation catalysis by the Fenton-like reagent involves homolysis of the oxygen-oxygen bond of the iron(III)hydro-peroxo species, producing an OH. radical and the ferryl ion (reaction 6.5). We have studied this reaction in detail, since it has emerged from our static DFT calculations as one of the most likely second reaction steps, in particular when the hydrolysis of a water ligand is simultaneously taken into account.

We have performed constrained AIMD simulations to calculate the

free energy profile for the oxygen-oxygen bond homolysis reaction

of the [Fe![]() (H

(H![]() O)

O)![]() OOH]

OOH]![]() complex into

an iron(IV)oxo species and an OH. radical in water. The oxygen-oxygen

bond length

complex into

an iron(IV)oxo species and an OH. radical in water. The oxygen-oxygen

bond length ![]() was taken as the constrained reaction coordinate,

which seems intuitively a good choice that includes the most important

contribution to the intrinsic reaction coordinate. The main drawback of

this choice is however that it does not prevent unwanted side reactions

such as the abstraction of solvent molecule hydrogens by the OH.

radical produced. For large values of the constrained

reaction coordinate

was taken as the constrained reaction coordinate,

which seems intuitively a good choice that includes the most important

contribution to the intrinsic reaction coordinate. The main drawback of

this choice is however that it does not prevent unwanted side reactions

such as the abstraction of solvent molecule hydrogens by the OH.

radical produced. For large values of the constrained

reaction coordinate ![]() , the OH. radical can abstract a

solvent hydrogen forming H

, the OH. radical can abstract a

solvent hydrogen forming H![]() O, while an OH. species "jumps" through

the solvent by a chain reaction. The sampled force

of constraint, associated with the force necessary to keep a H

O, while an OH. species "jumps" through

the solvent by a chain reaction. The sampled force

of constraint, associated with the force necessary to keep a H![]() O

molecule (instead of the OH.) constrained to the oxygen of the

iron complex, will then be of course meaningless.

We will therefore take the same approach as was done in the work by Trout and

Parrinello, who studied the dissociation of H

O

molecule (instead of the OH.) constrained to the oxygen of the

iron complex, will then be of course meaningless.

We will therefore take the same approach as was done in the work by Trout and

Parrinello, who studied the dissociation of H![]() O in water in H

O in water in H![]() and

OH

and

OH![]() with the

same technique,[207] and only calculated the profile up to

(or at least very close to) the transition state. Since the subsequent

reaction of the OH. "jumping" into the solvent is thermoneutral, the free energy

profile of the homolysis is not expected to decrease by more than a few kcal/mol

beyond the transition state (due to the increasing entropy of the leaving

OH. radical and the solvation of the oxo site).

Moreover, the transition state energy is the more important parameter

to determine whether the oxygen-oxygen homolysis is indeed a probable mechanism.

with the

same technique,[207] and only calculated the profile up to

(or at least very close to) the transition state. Since the subsequent

reaction of the OH. "jumping" into the solvent is thermoneutral, the free energy

profile of the homolysis is not expected to decrease by more than a few kcal/mol

beyond the transition state (due to the increasing entropy of the leaving

OH. radical and the solvation of the oxo site).

Moreover, the transition state energy is the more important parameter

to determine whether the oxygen-oxygen homolysis is indeed a probable mechanism.

|

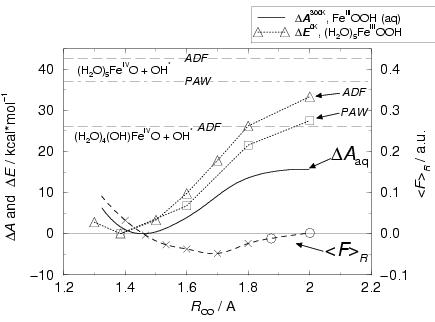

Eight constrained AIMD runs were performed with constrained oxygen-oxygen bond

lengths varying from

![]() Å.

The initial configuration of each constrained simulation was taken from

the last frame of the first simulation of hydroperoxo iron(III)

in water, including the hydronium ion (see section 6.3.2).

For each system, a short AIMD simulation was started to bring

Å.

The initial configuration of each constrained simulation was taken from

the last frame of the first simulation of hydroperoxo iron(III)

in water, including the hydronium ion (see section 6.3.2).

For each system, a short AIMD simulation was started to bring ![]() to

the desired value in 2000 steps. Then equilibration of each system took place

for 2 picoseconds, after which the force of constraint was accumulated for

another 2 picoseconds. The obtained values for the mean force of constraint

are denoted by crosses and circles in

figure 6.4 and fitted with a quadratic spline.

Integration of the mean force of constraint gives the Helmholtz free energy profile

to

the desired value in 2000 steps. Then equilibration of each system took place

for 2 picoseconds, after which the force of constraint was accumulated for

another 2 picoseconds. The obtained values for the mean force of constraint

are denoted by crosses and circles in

figure 6.4 and fitted with a quadratic spline.

Integration of the mean force of constraint gives the Helmholtz free energy profile

![]() , where we take the minimum at

, where we take the minimum at ![]() Å

for the offset of the energy scale (solid line). The circles indicate those constrained

simulations during which the O

Å

for the offset of the energy scale (solid line). The circles indicate those constrained

simulations during which the O![]() H. radical abstracts a hydrogen and

transforms into a water molecule. Indeed, this occurs for the

H. radical abstracts a hydrogen and

transforms into a water molecule. Indeed, this occurs for the

![]() values close to the transition state, for which the

O

values close to the transition state, for which the

O![]() H part has acquired enough radical character to abstract a hydrogen

when a nearby solvent molecule moves into a suitable position.

In both cases (at

H part has acquired enough radical character to abstract a hydrogen

when a nearby solvent molecule moves into a suitable position.

In both cases (at

![]() Å and at

Å and at

![]() Å),

the hydrogen abstraction occurs after about 1.3 ps simulation. The values for

the mean force of constraint denoted by the circles are the averages

over these 1.3 ps. After the H abstraction by O

Å),

the hydrogen abstraction occurs after about 1.3 ps simulation. The values for

the mean force of constraint denoted by the circles are the averages

over these 1.3 ps. After the H abstraction by O![]() H., the force of

constraint goes to zero, or becomes even slightly positive (repulsive)

because the produced water molecule is repelled by the oxo ligand at

the short constrained oxygen-oxygen distance, rather than attracted like

the OH. radical shortly before. For the O-O distance of

H., the force of

constraint goes to zero, or becomes even slightly positive (repulsive)

because the produced water molecule is repelled by the oxo ligand at

the short constrained oxygen-oxygen distance, rather than attracted like

the OH. radical shortly before. For the O-O distance of

![]() Å, the average force of constraint (over

the 1.3 ps before the H abstraction) is almost equal to zero,

which indicates that this O-O distance is indeed very close to the

transition state.

Å, the average force of constraint (over

the 1.3 ps before the H abstraction) is almost equal to zero,

which indicates that this O-O distance is indeed very close to the

transition state.

The free energy reaction barrier for the homolysis reaction in water

is found to be

![]() kcal/mol, which is low compared

to the

kcal/mol, which is low compared

to the ![]() kcal/mol (ground-state) energy change found

for the reaction in vacuo, or even the

kcal/mol (ground-state) energy change found

for the reaction in vacuo, or even the ![]() kcal/mol

for the hydrolyzed complexes in vacuo (reaction I in

table 6.1). We have also plotted twice the contour for the

reaction energy

kcal/mol

for the hydrolyzed complexes in vacuo (reaction I in

table 6.1). We have also plotted twice the contour for the

reaction energy

![]() of the homolysis of the

[Fe

of the homolysis of the

[Fe![]() (H

(H![]() O)

O)![]() OOH]

OOH]![]() complex in vacuo (triangles

connected by a dotted line, and the value for infinite product separation

indicated by the vertical dashed line); once computed with the ADF program

and once computed with the PAW program. Unfortunately, we find an

increasing underestimation of the energy profile with increasing

complex in vacuo (triangles

connected by a dotted line, and the value for infinite product separation

indicated by the vertical dashed line); once computed with the ADF program

and once computed with the PAW program. Unfortunately, we find an

increasing underestimation of the energy profile with increasing ![]() ,

calculated with PAW compared to the highly accurate (all-electron, large

basis set) ADF results, with a maximum difference of 5.6 kcal/mol

at

,

calculated with PAW compared to the highly accurate (all-electron, large

basis set) ADF results, with a maximum difference of 5.6 kcal/mol

at

![]() Å and at infinite separation. The error does not

seem to be due to the plane-wave cutoff of 30 Ry (it is only reduced by

0.5 kcal/mol when going to 50 Ry) and can be attributed to the partial

waves for the inner region of the valence electrons and the projector

functions for the iron atom used in the PAW calculations.

Although bond energies in iron(III) and iron(IV) complexes

computed with PAW agree within 2 kcal/mol with those using ADF, we

have found after extensive tests that the stability of the (formally)

Fe

Å and at infinite separation. The error does not

seem to be due to the plane-wave cutoff of 30 Ry (it is only reduced by

0.5 kcal/mol when going to 50 Ry) and can be attributed to the partial

waves for the inner region of the valence electrons and the projector

functions for the iron atom used in the PAW calculations.

Although bond energies in iron(III) and iron(IV) complexes

computed with PAW agree within 2 kcal/mol with those using ADF, we

have found after extensive tests that the stability of the (formally)

Fe![]() configuration is overestimated by 5-6 kcal/mol with respect

to the (formally) Fe

configuration is overestimated by 5-6 kcal/mol with respect

to the (formally) Fe![]() configuration.

This indicates that also the free energy barrier of the homolysis

in aqueous solution has to be corrected for this error so that

the true value becomes

configuration.

This indicates that also the free energy barrier of the homolysis

in aqueous solution has to be corrected for this error so that

the true value becomes

![]() kcal/mol.

Solvent effects thus strongly reduce the transition state barrier

for the O-O homolysis reaction in water. The main contribution to this

effect is expected to originate from the larger absolute energy of solvation

for the separating transition state complex (Fe

kcal/mol.

Solvent effects thus strongly reduce the transition state barrier

for the O-O homolysis reaction in water. The main contribution to this

effect is expected to originate from the larger absolute energy of solvation

for the separating transition state complex (Fe![]() =O

=O![]() OH.)

in comparison with the reactant molecule, Fe

OH.)

in comparison with the reactant molecule, Fe![]() OOH.

(Note that often reaction barriers are increased in aqueous solution,

because the sum of the absolute energies of solvation for two reacting

molecules is typically larger than that for the single transition state

complex.)

OOH.

(Note that often reaction barriers are increased in aqueous solution,

because the sum of the absolute energies of solvation for two reacting

molecules is typically larger than that for the single transition state

complex.)

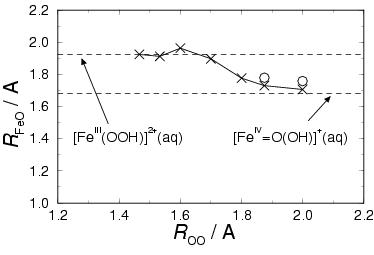

The upper graph in figure 6.5 illustrates the

transformation of the Fe![]() -OOH

-OOH![]() bond into an

Fe

bond into an

Fe![]() =O

=O![]() bond by showing the average

Fe-O

bond by showing the average

Fe-O![]() distance as a function of the reaction coordinate.

The two dashed lines indicate the average

distance as a function of the reaction coordinate.

The two dashed lines indicate the average ![]() for the

pentaaquairon(III)hydroperoxo complex in water (obtained from the

first 5 ps simulation described in section 6.3.2),

equal to 1.922 Å and the average

for the

pentaaquairon(III)hydroperoxo complex in water (obtained from the

first 5 ps simulation described in section 6.3.2),

equal to 1.922 Å and the average ![]() for the

ferryl ion in water equal to 1.680 Å. This latter number was

obtained from the [Fe

for the

ferryl ion in water equal to 1.680 Å. This latter number was

obtained from the [Fe![]() O(OH)]

O(OH)]![]() moiety produced in the

reaction between Fe

moiety produced in the

reaction between Fe![]() and H

and H![]() O

O![]() in water (cf.

ref bernd4), in which indeed a water ligand hydrolyzed to

form the OH

in water (cf.

ref bernd4), in which indeed a water ligand hydrolyzed to

form the OH![]() ligand as suggested in section 6.3.1.

This apparent increased acidity of the iron(IV) species compared

to that of iron(III) is discussed below.

Proceeding with the Fe-O distance, we see that

ligand as suggested in section 6.3.1.

This apparent increased acidity of the iron(IV) species compared

to that of iron(III) is discussed below.

Proceeding with the Fe-O distance, we see that ![]() decreases rapidly when the oxygen-oxygen separation becomes

larger than 1.7 Å, which indicates the changing character of the

metal and the bonds. At the reaction coordinate value of

decreases rapidly when the oxygen-oxygen separation becomes

larger than 1.7 Å, which indicates the changing character of the

metal and the bonds. At the reaction coordinate value of

![]() Å, the average

Å, the average ![]() (over the 1.3 ps simulation

before the O

(over the 1.3 ps simulation

before the O![]() H. radical abstracts a solvent hydrogen) has decreased

practically to the average value of free [Fe

H. radical abstracts a solvent hydrogen) has decreased

practically to the average value of free [Fe![]() O(OH)]

O(OH)]![]() ,

which indicates that at

,

which indicates that at

![]() Å the reaction is close

to completion. The open circles in figure 6.5 denote

the averages over the simulation part after the O

Å the reaction is close

to completion. The open circles in figure 6.5 denote

the averages over the simulation part after the O![]() H. radical

transformed into H

H. radical

transformed into H![]() O

O![]() by H-abstraction from an adjacent solvent

molecule. At

by H-abstraction from an adjacent solvent

molecule. At

![]() Å, the average

Å, the average ![]() is a little

larger than expected from the trend. This is the result of proton donation

from the iron complex (i.e. hydrolysis) to the aqueous solvent

during the constrained simulation at this reaction coordinate value,

which we will explain below.

is a little

larger than expected from the trend. This is the result of proton donation

from the iron complex (i.e. hydrolysis) to the aqueous solvent

during the constrained simulation at this reaction coordinate value,

which we will explain below.

|

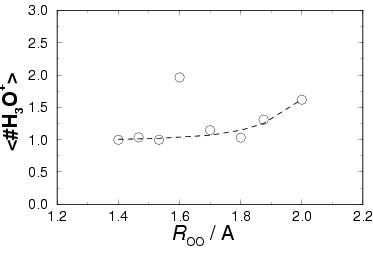

As mentioned before, we expect hydrolysis of water ligands to lower

the reaction energy of the oxygen-oxygen homolysis (see the change from

42.6 to 26.1 kcal/mol for reaction I in table 6.1), and secondly

we expect hydrolysis to become more frequent for iron(IV) (product)

compared to iron(III) (reactant). In our short constrained dynamics

simulations of the enforced O![]() -O

-O![]() homolysis in aqueous

solution, we can

indeed observe these trends by plotting the average number of

hydronium ions in the solvent versus the reaction coordinate

homolysis in aqueous

solution, we can

indeed observe these trends by plotting the average number of

hydronium ions in the solvent versus the reaction coordinate ![]() (see circles in the lower graph in figure 6.5

and the dotted lines to guide the eye). The water ligand O-H distances

(see circles in the lower graph in figure 6.5

and the dotted lines to guide the eye). The water ligand O-H distances

![]() were taken as the order parameters: all

10

were taken as the order parameters: all

10

![]() Å means that no hydrolysis has taken place.

At the reactant side (small

Å means that no hydrolysis has taken place.

At the reactant side (small ![]() ),

hydrolysis is rarely observed during the 2 ps simulations and only

the one hydronium ion which we started with (originating from the

hydrogen peroxide when it reacted with iron(III), see previous sections)

brings the average number to 1 H

),

hydrolysis is rarely observed during the 2 ps simulations and only

the one hydronium ion which we started with (originating from the

hydrogen peroxide when it reacted with iron(III), see previous sections)

brings the average number to 1 H![]() O

O![]() . Going towards higher

. Going towards higher

![]() values, the oxidation state of the iron ion goes

to four and the complex is seen to become more acidic, confirming the

second trend mentioned. At

values, the oxidation state of the iron ion goes

to four and the complex is seen to become more acidic, confirming the

second trend mentioned. At

![]() Å,

62 % of the time a (second) proton was donated to the solvent by the complex

(in the 1.3 ps before H abstraction by the leaving O

Å,

62 % of the time a (second) proton was donated to the solvent by the complex

(in the 1.3 ps before H abstraction by the leaving O![]() H.

from a solvent water), which justifies the previous comparison of

H.

from a solvent water), which justifies the previous comparison of ![]() with that of the hydrolyzed ferryl ion ([Fe

with that of the hydrolyzed ferryl ion ([Fe![]() O(OH)]

O(OH)]![]() )

in the upper graph.

At

)

in the upper graph.

At

![]() Å, the average number of 1.96 hydronium ions seems out

of order in this trend. In the simulations, we see that for this run the

two hydronium ions are most of the time jumping freely around in the

solvent. In the other runs however, we find that most of the time

one of the protons jumps back and forth between the ligand and a solvent

water molecule and thus remains in the neighborhood of the complex.

Apparently we can separate the ligand hydrolysis into two stages which

show resemblance with the dynamics of free hydronium ion transfer

in water (cf. ref. TLSP2), namely:

1) a fast process which involves the sharing of the proton

by a ligand and a solvent molecule (or two solvent waters for the

free hydronium ion, with a frequency

Å, the average number of 1.96 hydronium ions seems out

of order in this trend. In the simulations, we see that for this run the

two hydronium ions are most of the time jumping freely around in the

solvent. In the other runs however, we find that most of the time

one of the protons jumps back and forth between the ligand and a solvent

water molecule and thus remains in the neighborhood of the complex.

Apparently we can separate the ligand hydrolysis into two stages which

show resemblance with the dynamics of free hydronium ion transfer

in water (cf. ref. TLSP2), namely:

1) a fast process which involves the sharing of the proton

by a ligand and a solvent molecule (or two solvent waters for the

free hydronium ion, with a frequency ![]() 5 ps

5 ps![]() )

and 2) a much slower process, which is connected to

the actual stepwise diffusion of the hydronium ion through the solvent.

The latter process concerns changes in the second coordination

shell hydrogen bond

network which in water was found to have a frequency of about

0.5 ps

)

and 2) a much slower process, which is connected to

the actual stepwise diffusion of the hydronium ion through the solvent.

The latter process concerns changes in the second coordination

shell hydrogen bond

network which in water was found to have a frequency of about

0.5 ps![]() .[53] Obviously, our 2 ps AIMD simulations are

too short to capture good statistics of the slow process, so that

in each simulation we either see the excess proton being shared

by two water molecules in the solvent (namely in the run with

.[53] Obviously, our 2 ps AIMD simulations are

too short to capture good statistics of the slow process, so that

in each simulation we either see the excess proton being shared

by two water molecules in the solvent (namely in the run with

![]() Å,) or it is being shared by a ligand and a

solvent molecule (as in all other runs). Fortunately, already from the

distribution in the fast jumping process we obtain information

on the acidity (i.e. the ability to donate a proton to

the aqueous environment) of the iron complex, as shown in figure

6.5, but for comparison with experimental p

Å,) or it is being shared by a ligand and a

solvent molecule (as in all other runs). Fortunately, already from the

distribution in the fast jumping process we obtain information

on the acidity (i.e. the ability to donate a proton to

the aqueous environment) of the iron complex, as shown in figure

6.5, but for comparison with experimental p![]() values we need to include also the slower hydronium ion transport.

The run with

values we need to include also the slower hydronium ion transport.

The run with

![]() Å confirms the first trend

mentioned in this paragraph: replacement of a water ligand

by a hydroxo ligand facilitates the oxygen-oxygen homolysis. In

our constrained MD exercise this is seen by the lower absolute constraint

force resulting in a dent in the mean constraint force profile in

figure 6.4 and also in the

Å confirms the first trend

mentioned in this paragraph: replacement of a water ligand

by a hydroxo ligand facilitates the oxygen-oxygen homolysis. In

our constrained MD exercise this is seen by the lower absolute constraint

force resulting in a dent in the mean constraint force profile in

figure 6.4 and also in the ![]() profile in figure 6.5. If we could afford

better statistics by performing much longer simulations,

in principle the two states (pentaaqua versus hydrolyzed tetraaqua

hydroxo complex) would be sampled with correct weights, giving the

correct mean force of constraint and free energy profile. In our

result however, we find for all runs except the one with

profile in figure 6.5. If we could afford

better statistics by performing much longer simulations,

in principle the two states (pentaaqua versus hydrolyzed tetraaqua

hydroxo complex) would be sampled with correct weights, giving the

correct mean force of constraint and free energy profile. In our

result however, we find for all runs except the one with

![]() Å

mostly the pentaaqua complex, so that we should take into account an

overestimation of a few kcal/mol for the free energy barrier.

Moreover, if we would be interested in calculating the reaction

rate of the O-O homolysis reaction in water we should either control the

hydrolysis process by including it in the reaction coordinate or

we should expect a large deviation from the transition state theory

reaction rate, and therefore perform the cumbersome computation

of the transmission coefficient in the pre-exponential factor.

We can nevertheless conclude that our estimation of the free energy

barrier of the O-O homolysis of the iron(III)hydroperoxo intermediate

in aqueous solution indicates that this formation of a ferryl ion

and the OH. radical is a likely second step in Fenton-like chemistry.

And secondly, the simulations confirm the hypothesis that water ligand

hydrolysis plays an important role in the process.

Å

mostly the pentaaqua complex, so that we should take into account an

overestimation of a few kcal/mol for the free energy barrier.

Moreover, if we would be interested in calculating the reaction

rate of the O-O homolysis reaction in water we should either control the

hydrolysis process by including it in the reaction coordinate or

we should expect a large deviation from the transition state theory

reaction rate, and therefore perform the cumbersome computation

of the transmission coefficient in the pre-exponential factor.

We can nevertheless conclude that our estimation of the free energy

barrier of the O-O homolysis of the iron(III)hydroperoxo intermediate

in aqueous solution indicates that this formation of a ferryl ion

and the OH. radical is a likely second step in Fenton-like chemistry.

And secondly, the simulations confirm the hypothesis that water ligand

hydrolysis plays an important role in the process.