a) Formation.

In this section, we will describe the results of our study of the most

likely intermediate formed in a mixture of iron(III) ions and hydrogen

peroxide in water. We will follow the same approach as in

our previous work[146] on the active intermediate formed from iron(II) and

hydrogen peroxide, which makes it easy to compare the reactions with

each other. In this previous work on Fenton's reagent, we showed two

illustrative pathways of the reaction between Fe![]() and

H

and

H![]() O

O![]() in water producing the high-valent iron-oxo species

[Fe

in water producing the high-valent iron-oxo species

[Fe![]() O]

O]![]() . The ferryl ion formation occurred either in two steps,

via an iron(IV) dihydroxo intermediate ([Fe

. The ferryl ion formation occurred either in two steps,

via an iron(IV) dihydroxo intermediate ([Fe![]() (OH)

(OH)![]() ]

]![]() ),

if we started from a [Fe

),

if we started from a [Fe![]() (H

(H![]() O

O![]() )]

)]![]() complex, or

via a more direct ``rebound'' mechanism if we started from separated

Fe

complex, or

via a more direct ``rebound'' mechanism if we started from separated

Fe![]() and H

and H![]() O

O![]() , thus including the coordination process of H

, thus including the coordination process of H![]() O

O![]() to an empty iron(II) site. The [Fe

to an empty iron(II) site. The [Fe![]() (H

(H![]() O

O![]() )]

)]![]() complex

was not found to be a stable intermediate in aqueous solution, unlike

[(H

complex

was not found to be a stable intermediate in aqueous solution, unlike

[(H![]() O)

O)![]() Fe

Fe![]() (H

(H![]() O

O![]() )]

)]![]() in vacuo.

in vacuo.

For the present reaction of hydrogen peroxide with iron(III), we performed

a Car-Parrinello MD simulation of H![]() O

O![]() coordinated to Fe

coordinated to Fe![]() ,

surrounded by 31 water molecules in a cubic box with periodic boundary

conditions. We used a snapshot from the study of the

[Fe

,

surrounded by 31 water molecules in a cubic box with periodic boundary

conditions. We used a snapshot from the study of the

[Fe![]() (H

(H![]() O

O![]() )]

)]![]() complex in water for the initial

configuration, and removed in that configuration one spin-down electron from the system.

The total spin was thus

complex in water for the initial

configuration, and removed in that configuration one spin-down electron from the system.

The total spin was thus ![]() , and the total charge

equaled 3+, which was counterbalanced by a uniformly distributed

3- charge. We relaxed the system to the new situation, by an MD

run of 3.5 ps. During this time of equilibration, bond constraints

were applied to the Fe-O and O-O bonds, fixing these bond lengths to their

equilibrium distances, in order to prevent a premature breakup of the

complex by the unrelaxed environment. Next, we removed the constraints

and followed the evolution of the [Fe

, and the total charge

equaled 3+, which was counterbalanced by a uniformly distributed

3- charge. We relaxed the system to the new situation, by an MD

run of 3.5 ps. During this time of equilibration, bond constraints

were applied to the Fe-O and O-O bonds, fixing these bond lengths to their

equilibrium distances, in order to prevent a premature breakup of the

complex by the unrelaxed environment. Next, we removed the constraints

and followed the evolution of the [Fe![]() (H

(H![]() O

O![]() )]

)]![]() complex in water for 5 ps.

complex in water for 5 ps.

Already in the equilibration phase, hydrolysis had taken place on the

![]() -oxygen of the ligated hydrogen peroxide (

-oxygen of the ligated hydrogen peroxide (![]() denotes

the oxygen connected to iron), donating the proton to the water solvent:

denotes

the oxygen connected to iron), donating the proton to the water solvent:

![\begin{displaymath}

\left[(\mathrm{H}_2\mathrm{O})_5\mathrm{Fe^{III}}(\mathrm{H...

...{III}}(\mathrm{OOH})\right]^{2+} +

\mathrm{H}_3\mathrm{O}^{+}

\end{displaymath}](img600.png) |

(72) |

Our simulation thus started with an iron(III)hydroperoxo complex

and a hydronium ion in water, and no further spontaneous transformation took

place during the 5 ps of molecular dynamics. The oxygen-oxygen bond did not

break but instead fluctuated around an average bond length of

![]() Å, contrary to the

oxygen-oxygen bond of hydrogen peroxide coordinated to iron(II)

which was found to cleave spontaneously in aqueous solution.

Also was the aqueous proton not seen to jump back on the hydroperoxo ligand

during our simulation, as with the dynamic equilibria we have for instance

seen for hydrolysis of aqua ligands of hexaaquairon(III) (see

before) and the [(H

Å, contrary to the

oxygen-oxygen bond of hydrogen peroxide coordinated to iron(II)

which was found to cleave spontaneously in aqueous solution.

Also was the aqueous proton not seen to jump back on the hydroperoxo ligand

during our simulation, as with the dynamic equilibria we have for instance

seen for hydrolysis of aqua ligands of hexaaquairon(III) (see

before) and the [(H![]() O)

O)![]() Fe

Fe![]() (OH)

(OH)![]() ]

]![]() complex.[171]

The OH bond length fluctuations of the aqua ligands were significantly

larger than the ones in hexaaquairon(II), with maxima

of

complex.[171]

The OH bond length fluctuations of the aqua ligands were significantly

larger than the ones in hexaaquairon(II), with maxima

of

![]() Å

(

Å

(

![]() Å in hexaaquairon(II)), almost

donating a proton to the solvent, but never dissociating completely.

This indicates that the acidity of [(H

Å in hexaaquairon(II)), almost

donating a proton to the solvent, but never dissociating completely.

This indicates that the acidity of [(H![]() O)

O)![]() Fe

Fe![]() (OOH)]

(OOH)]![]() is in between that of hexaaquairon(II) and hexaaquairon(III).

is in between that of hexaaquairon(II) and hexaaquairon(III).

To make sure that the hydroperoxo ligand formation (during the equilibration

phase) was not the result of non-equilibrium solvent effects, we started a

second MD simulation from a configuration of the equilibration phase

at a time just before the hydrogen peroxide hydrolysis took place.

This time, we constrained the O![]() -H bond length

to prevent hydrolysis during a 1.2 ps equilibration

run, after which we removed the constraint and again followed the

evolution of the system. Although during most of the equilibration time

now an aqua ligand donated a proton to the solvent (reaction equation

6.8),

-H bond length

to prevent hydrolysis during a 1.2 ps equilibration

run, after which we removed the constraint and again followed the

evolution of the system. Although during most of the equilibration time

now an aqua ligand donated a proton to the solvent (reaction equation

6.8),

this proton is united with the hydroxo ligand again

at the end of the equilibration so that indeed we started with a

[(H![]() O)

O)![]() Fe

Fe![]() (H

(H![]() O

O![]() )]

)]![]() complex in water.

After 0.2 ps, again hydrolysis of the coordinated hydrogen peroxide

takes place so that the Fe

complex in water.

After 0.2 ps, again hydrolysis of the coordinated hydrogen peroxide

takes place so that the Fe![]() OOH moiety is formed which again remains

stable for the next 1.75 ps, after which we stopped the computation.

Clearly, this second simulation shows that the H

OOH moiety is formed which again remains

stable for the next 1.75 ps, after which we stopped the computation.

Clearly, this second simulation shows that the H![]() O

O![]() ligand hydrolysis

was not an effect of the unrelaxed environment (which was not clear from

the first simulation). And secondly, the higher stability of the O-O bond

compared to the iron(II)hydrogen-peroxide case is not a result of the

H

ligand hydrolysis

was not an effect of the unrelaxed environment (which was not clear from

the first simulation). And secondly, the higher stability of the O-O bond

compared to the iron(II)hydrogen-peroxide case is not a result of the

H![]() O

O![]() hydrolysis, since no O-O lysis occurred spontaneously when only the

O

hydrolysis, since no O-O lysis occurred spontaneously when only the

O![]() -H bond length was constrained.

-H bond length was constrained.

Finally, we performed a last AIMD simulation in which we also wanted

to include the formation of a coordination bond of hydrogen peroxide to

a vacant coordination

site of iron(III). Starting with a random configuration in which the solvated

reactants are separated from each other a certain distance is however

very unpractical, because the probability of a spontaneous coordination is too

small to make an observation likely in the relatively short time of a typical

AIMD simulation.

We therefore applied a simple device, which had worked already very well

for the iron(II)/H![]() O

O![]() system.[146] We carried out a

constrained AIMD simulation of hydrogen peroxide coordinated to iron(III)

in water. The O-O bond, the Fe-O

system.[146] We carried out a

constrained AIMD simulation of hydrogen peroxide coordinated to iron(III)

in water. The O-O bond, the Fe-O![]() bond and the O

bond and the O![]() -H bond

were fixed to their equilibrium distances and also a bond constraint was

applied to the distance between the peroxide's O

-H bond

were fixed to their equilibrium distances and also a bond constraint was

applied to the distance between the peroxide's O![]() and the hydrogen

of an adjacent water ligand, fixing this distance to

and the hydrogen

of an adjacent water ligand, fixing this distance to

![]() Å. The small

strain induced in the five-membered ring which is closed by the

Å. The small

strain induced in the five-membered ring which is closed by the ![]() constraint (see also figure 6.1) was enough to pull

hydrogen peroxide from the aquairon complex when we released all constraints,

except the O

constraint (see also figure 6.1) was enough to pull

hydrogen peroxide from the aquairon complex when we released all constraints,

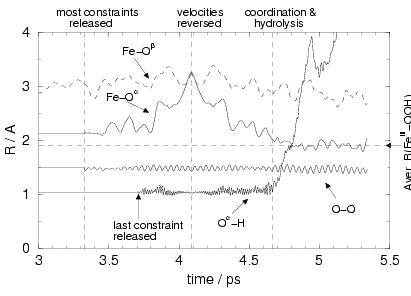

except the O![]() -H bond constraint. This process is illustrated in

figure 6.2, showing the distances Fe-O

-H bond constraint. This process is illustrated in

figure 6.2, showing the distances Fe-O![]() ,

Fe-O

,

Fe-O![]() , O

, O![]() -O

-O![]() and O

and O![]() -H as a function of time,

starting just before the moment we released these bond constraints.

-H as a function of time,

starting just before the moment we released these bond constraints.

|

After release of all constraints except the O![]() -H bond

constraint, at

-H bond

constraint, at ![]() ps, the Fe-O

ps, the Fe-O![]() bond starts to break,

which is visible in figure 6.2 as the appearance of

oscillations with increasing amplitude of

bond starts to break,

which is visible in figure 6.2 as the appearance of

oscillations with increasing amplitude of

![]() , and

at

, and

at ![]() ps, Fe and O

ps, Fe and O![]() clearly separate. During the dissociation

process, at

clearly separate. During the dissociation

process, at ![]() ps, we also released the O

ps, we also released the O![]() H bond constraint.

At time

H bond constraint.

At time ![]() ps, we now have a situation where the Fe-O

ps, we now have a situation where the Fe-O![]() distance has increased to more than 3 Å i.e. the iron aqua

complex and H

distance has increased to more than 3 Å i.e. the iron aqua

complex and H![]() O

O![]() are separated from each other by at least 3 Å,

with velocities that will lead to further separation.

At this point, we reverse all the velocities

(including those of the electronic wave function degrees of freedom

and the Nosé thermostat variable) so that the reactants will now

approach each other in the same way as they separated. The difference

of course is that the O

are separated from each other by at least 3 Å,

with velocities that will lead to further separation.

At this point, we reverse all the velocities

(including those of the electronic wave function degrees of freedom

and the Nosé thermostat variable) so that the reactants will now

approach each other in the same way as they separated. The difference

of course is that the O![]() -H is now free to dissociate. In figure

6.2, we indeed see that as soon as hydrogen peroxide

coordinates to the Fe

-H is now free to dissociate. In figure

6.2, we indeed see that as soon as hydrogen peroxide

coordinates to the Fe![]() ion, the O

ion, the O![]() -H bond breaks, the

proton moves into the solvent and the iron(III)hydroperoxo complex is

being formed.

-H bond breaks, the

proton moves into the solvent and the iron(III)hydroperoxo complex is

being formed.

These illustrative pathways, confirm our inference from the calculation in vacuum

(table 6.1), that formation of the Fe(III)(OOH)

species is a likely candidate for the initial step in the Fenton-like reaction,

in agreement with experiment, and secondly, that the oxygen-oxygen bond

does not break so easily as in hydrogen peroxide coordinated to iron(II),

which ultimately led to the ferryl ion as the most likely active intermediate in the

Fe(II) catalysis.

Moreover, formation of [Fe![]() (H

(H![]() O)

O)![]() (OOH)]

(OOH)]![]() seems much more likely

than formation of [Fe

seems much more likely

than formation of [Fe![]() (H

(H![]() O)

O)![]() (OH)(H

(OH)(H![]() O

O![]() )]

)]![]() ,

in agreement with table 6.1.

This implies that as the second step of the Fenton-like reaction we should

investigate the subsequent transformation of Fe(III)(OOH). This will be

done in subsection 6.3.3. However, we will first investigate further the

iron(III)hydroperoxo complex itself, making a connection with the experimental

characterization of this moiety by vibrational spectroscopy of this

metal-ligand system in various solvents and with different ligand environments.

,

in agreement with table 6.1.

This implies that as the second step of the Fenton-like reaction we should

investigate the subsequent transformation of Fe(III)(OOH). This will be

done in subsection 6.3.3. However, we will first investigate further the

iron(III)hydroperoxo complex itself, making a connection with the experimental

characterization of this moiety by vibrational spectroscopy of this

metal-ligand system in various solvents and with different ligand environments.

|

b) Characterization: Fe(III)-OOH vibrations.

Spectroscopic experiments have indicated that the spin-state of Fe(III)OOH

complexes has a strong effect on the Fe-O and the O-O bond

strengths[199,200]. Resonance Raman spectroscopy on

low-spin iron(III)hydroperoxo complexes with large ligands such as

N4Py (![]() ,

,![]() -bis-(2-pyridylmethyl)-

-bis-(2-pyridylmethyl)-![]() -bis(2-pyridyl)methylamine)[201],

TPA (tris-(2-pyridylmethyl)-amine)[200] and TPEN

(

-bis(2-pyridyl)methylamine)[201],

TPA (tris-(2-pyridylmethyl)-amine)[200] and TPEN

(![]() ,

,![]() ,

,![]() ',

',![]() '-tetrakis-(2-pyridylmethyl)-ethane-1,2-diamine)[202]

show O-O vibrations with frequencies

between 789-801 cm

'-tetrakis-(2-pyridylmethyl)-ethane-1,2-diamine)[202]

show O-O vibrations with frequencies

between 789-801 cm![]() and Fe-O vibrations between 617-632 cm

and Fe-O vibrations between 617-632 cm![]() .

High-spin complexes show stronger O-O bonds

(

.

High-spin complexes show stronger O-O bonds

(

![]()

![]() 844 cm

844 cm![]() )

and weaker Fe-O bonds (

)

and weaker Fe-O bonds (

![]()

![]() 503 cm

503 cm![]() ).

The spin-state is normally dictated by the ligand field splitting

10

).

The spin-state is normally dictated by the ligand field splitting

10![]() caused by the ligands, but in our computer experiments we

can simply fix the number of spin-up and spin-down electrons.

We have thus calculated the Fe(III)OOH frequencies of the complex

in water at

caused by the ligands, but in our computer experiments we

can simply fix the number of spin-up and spin-down electrons.

We have thus calculated the Fe(III)OOH frequencies of the complex

in water at ![]() K for both spin states. This was done by performing

an AIMD simulation

for each spin-state starting from the last frame of the first

simulation of Fe(III)OOH (see previous section). The hydronium

ion in the solvent was replaced with a water molecule to avoid the

influence it could have on the vibrations of the complex. We calculated

a 2.5 ps AIMD trajectory, from which the last 1.5 ps was used to

calculate the velocity autocorrelation of specific vibrations, such as

the oxygen-oxygen bond stretching

K for both spin states. This was done by performing

an AIMD simulation

for each spin-state starting from the last frame of the first

simulation of Fe(III)OOH (see previous section). The hydronium

ion in the solvent was replaced with a water molecule to avoid the

influence it could have on the vibrations of the complex. We calculated

a 2.5 ps AIMD trajectory, from which the last 1.5 ps was used to

calculate the velocity autocorrelation of specific vibrations, such as

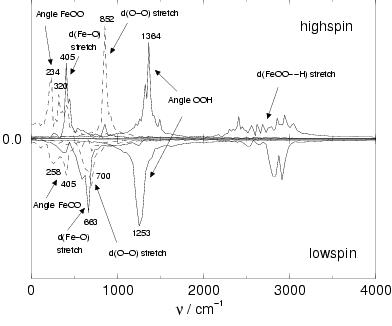

the oxygen-oxygen bond stretching ![]() . The Fourier

transformation of these velocity autocorrelation functions gives

the vibration spectra shown in figure 6.3.

The peaks shown in figure 6.3 are rather broad

which is partly due to the relatively short simulation time (limited

statistics). Nevertheless, the statistics are sufficient to clearly resolve

the large differences between the low-spin and the high-spin spectra.

. The Fourier

transformation of these velocity autocorrelation functions gives

the vibration spectra shown in figure 6.3.

The peaks shown in figure 6.3 are rather broad

which is partly due to the relatively short simulation time (limited

statistics). Nevertheless, the statistics are sufficient to clearly resolve

the large differences between the low-spin and the high-spin spectra.

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

| low-spin calculations | |||||

| (H |

253, 326 | 626 | 810 | 1291 | 3544 |

|

|

|||||

| (H |

258, 405 | 663 | 700 | 1253 | 2500-3000 |

|

|

|||||

| -experiment- | |||||

| [(N4Py)Fe(OOH)] |

632 | 790 | |||

| [(TPA)Fe(OOH)] |

626 | 789 | |||

| [(TPEN)Fe(OOH)] |

617 | 796 | |||

| [(trispicen)Fe(OOH)] |

625 | 801 | |||

| [(trispicMeen)Fe(OOH)] |

617 | 796 | |||

| high-spin calculations | |||||

| (H |

180, 209 | 445 | 980 | 1366 | 3514 |

|

|

|||||

| (H |

234, 320 | 405 | 852 | 1364 | 2000-3000 |

|

|

|||||

| -experiment- | |||||

| [(TPEN)Fe(- |

468 | 821 | |||

| [(trispicMeen)Fe(- |

468 | 820 | |||

| [Fe(EDTA)(- |

459 | 816 | |||

| [Fe(EDTA)(- |

472 | 824 | |||

| Oxyhemerythrin(- |

503 | 844 | |||

The OH stretch vibration in the hydroperoxo ligand gives rise to a

broad region of peaks around 2500-3000 cm![]() in the

in the ![]() state,

whereas these peaks are more localized in the low-spin state. In the

simulation (and also in experiments[206]), the OH stretch

frequency decreases when the hydrogen forms a hydrogen bond with a

solvent water molecule. The shorter (stronger) the hydrogen bond, the

lower the OH frequency. The average hydrogen bond length between the hydroperoxo

hydrogen and the nearest solvent oxygen is 0.08 Å shorter in the

high-spin state than in the low-spin state, while the average OH bond length

in the hydroperoxo ligand is 0.01 Å longer. This could be an indication

that the hydroperoxo ligand is more easily deprotonated in high-spin complexes,

giving rise to the peroxo ligand, than in low-spin complexes.

state,

whereas these peaks are more localized in the low-spin state. In the

simulation (and also in experiments[206]), the OH stretch

frequency decreases when the hydrogen forms a hydrogen bond with a

solvent water molecule. The shorter (stronger) the hydrogen bond, the

lower the OH frequency. The average hydrogen bond length between the hydroperoxo

hydrogen and the nearest solvent oxygen is 0.08 Å shorter in the

high-spin state than in the low-spin state, while the average OH bond length

in the hydroperoxo ligand is 0.01 Å longer. This could be an indication

that the hydroperoxo ligand is more easily deprotonated in high-spin complexes,

giving rise to the peroxo ligand, than in low-spin complexes.

The O-O stretch vibration decreases from 852 cm![]() to 700 cm

to 700 cm![]() when

going from the high-spin state to the low-spin state and the Fe-O stretch

vibration increases from 405 cm

when

going from the high-spin state to the low-spin state and the Fe-O stretch

vibration increases from 405 cm![]() to 663 cm

to 663 cm![]() , in agreement with

the trend found with Raman spectroscopy for different complexes.

For comparison, we have also optimized the geometry for the

[Fe

, in agreement with

the trend found with Raman spectroscopy for different complexes.

For comparison, we have also optimized the geometry for the

[Fe![]() (H

(H![]() O)

O)![]() (OOH)]

(OOH)]![]() complex in vacuo

for the

complex in vacuo

for the ![]() state and the

state and the ![]() state, and calculated the vibrational

frequencies in the harmonic approximation. The results are shown in

table 6.2, together with a compilation of values

for the O-O and Fe-O stretch vibrations obtained using Raman spectroscopy

on several low-spin and high-spin complexes. The O-O stretch vibration is

significantly lower in the solvent than in the gas phase complex.

This decrease, indicating a weakening of the O-O bond in aqueous

solution, is due to the interaction of solvent water molecules with

the hydroperoxo group. Not only the hydrogen, but also both oxygens

are involved in hydrogen bonds with the solvent. Integration of the

radial distribution functions (data not shown) obtained from the first 5 ps simulation

of high-spin Fe(III)OOH in water (see previous paragraph) gives an average

of 1.6 solvent hydrogens within a 2.3 Å radius of O

state, and calculated the vibrational

frequencies in the harmonic approximation. The results are shown in

table 6.2, together with a compilation of values

for the O-O and Fe-O stretch vibrations obtained using Raman spectroscopy

on several low-spin and high-spin complexes. The O-O stretch vibration is

significantly lower in the solvent than in the gas phase complex.

This decrease, indicating a weakening of the O-O bond in aqueous

solution, is due to the interaction of solvent water molecules with

the hydroperoxo group. Not only the hydrogen, but also both oxygens

are involved in hydrogen bonds with the solvent. Integration of the

radial distribution functions (data not shown) obtained from the first 5 ps simulation

of high-spin Fe(III)OOH in water (see previous paragraph) gives an average

of 1.6 solvent hydrogens within a 2.3 Å radius of O![]() and 0.8

(other) solvent hydrogens within a 2.3 Å radius of O

and 0.8

(other) solvent hydrogens within a 2.3 Å radius of O![]() .

Surprisingly, the static DFT results in vacuo for the low-spin O-O and Fe-O

vibrations compare better with the experimental results than the ones

obtained from the dynamics in aqueous solution at

.

Surprisingly, the static DFT results in vacuo for the low-spin O-O and Fe-O

vibrations compare better with the experimental results than the ones

obtained from the dynamics in aqueous solution at ![]() K. This could

be due to (again) the aqueous solvent interactions with the

hydroperoxo ligand in the simulation, whereas the Raman spectroscopy

studies using the hydrophobic pyridine based ligands as N4Py, TPA, TPEN,

trispicen and trispicMeen typically took place

in solvents such as acetone and acetonitrile. Another factor is of course

the ligand field on the aqua ligated iron in the simulation, which is quite

different from the ligand fields on iron complexed by these large nitrogen

multidentate ligands used in the experiments.

Comparison of our high-spin results with the only

K. This could

be due to (again) the aqueous solvent interactions with the

hydroperoxo ligand in the simulation, whereas the Raman spectroscopy

studies using the hydrophobic pyridine based ligands as N4Py, TPA, TPEN,

trispicen and trispicMeen typically took place

in solvents such as acetone and acetonitrile. Another factor is of course

the ligand field on the aqua ligated iron in the simulation, which is quite

different from the ligand fields on iron complexed by these large nitrogen

multidentate ligands used in the experiments.

Comparison of our high-spin results with the only ![]() -OOH complex listed, namely

oxyhemerythrin in aqueous solution, indicates that both factors could play a role:

the Raman O-O stretch vibration agrees now much better with the AIMD result as

in both results the solvent used is water which interacts with the hydroperoxo ligand,

and secondly, the Fe-O stretch vibrations are still a bit off due to the different

ligand field (note that oxyhemerythrin is a diiron species: L-Fe(III)-O-Fe(III)-OOH).

-OOH complex listed, namely

oxyhemerythrin in aqueous solution, indicates that both factors could play a role:

the Raman O-O stretch vibration agrees now much better with the AIMD result as

in both results the solvent used is water which interacts with the hydroperoxo ligand,

and secondly, the Fe-O stretch vibrations are still a bit off due to the different

ligand field (note that oxyhemerythrin is a diiron species: L-Fe(III)-O-Fe(III)-OOH).

Concluding, we find that indeed the spin-state is an important factor for the O-O bond and Fe-O bond strengths in Fe(III)OOH complexes. The ligands (chelating agents) used in Fenton-like chemistry are therefore expected to directly influence the chemistry, because ligands inducing a large ligand field give rise to low-spin Fe(III)OOH complexes with stronger Fe-O bonds and weaker O-O bonds compared to the Fe-O and O-O bonds in the high-spin complexes which occur with ligands inducing a small ligand field. For the suggested second-step reactions following the initial Fe(III)OOH formation (reactions 6.4 till 6.6), the low-spin complexes thus promote the steps involving O-O lysis but make the steps involving Fe-O bond breaking even more unfavorable.