H

Transition metal catalyzed reactions are often assumed to start with

coordination of a reactant to the transition metal ion by a ligand

substitution reaction. If the substitution reaction is dissociative,

a vacant coordination site is first created, which is frequently

induced by thermal or photochemical means. The relative probability

of a dissociative mechanism for the substitution of a H![]() O ligand

for H

O ligand

for H![]() O

O![]() in the Fenton reaction is not known. However, rather

than starting from the coordinated H

in the Fenton reaction is not known. However, rather

than starting from the coordinated H![]() O

O![]() as in section 5.3.2,

we wish to investigate in the present section whether formation of an iron

oxo species is also probable when we start from a vacant coordination site

to which the hydrogen peroxide will coordinate in the first step of the reaction.

The energetic requirements will be essentially different

since the 23 kcal/mol bond energy of H

as in section 5.3.2,

we wish to investigate in the present section whether formation of an iron

oxo species is also probable when we start from a vacant coordination site

to which the hydrogen peroxide will coordinate in the first step of the reaction.

The energetic requirements will be essentially different

since the 23 kcal/mol bond energy of H![]() O

O![]() to pentaaquairon(II)

will become available in this first step. So in this section we present

the results of the AIMD simulation of a

reaction pathway for the reaction of hydrogen peroxide with an aqua

iron(II) complex containing a vacant coordination site.

Waiting for the spontaneous diffusion of

H

to pentaaquairon(II)

will become available in this first step. So in this section we present

the results of the AIMD simulation of a

reaction pathway for the reaction of hydrogen peroxide with an aqua

iron(II) complex containing a vacant coordination site.

Waiting for the spontaneous diffusion of

H![]() O

O![]() to the vacant iron site could take a very long time in an

AIMD simulation, simply because the reactants are as likely to

separate as to approach each other and secondly because the vacant

iron site is more likely to be occupied by one of the solvent water

molecules than by the single H

to the vacant iron site could take a very long time in an

AIMD simulation, simply because the reactants are as likely to

separate as to approach each other and secondly because the vacant

iron site is more likely to be occupied by one of the solvent water

molecules than by the single H![]() O

O![]() . To increase the probability

of observing a reactive encounter we need a favorable set of momenta for

the reactants and the solvating water molecules to start with. In the

following we will describe the method we used to obtain such a set of

momenta for a configuration of separated reactants in water followed

by the simulation of the reactive pathway.

. To increase the probability

of observing a reactive encounter we need a favorable set of momenta for

the reactants and the solvating water molecules to start with. In the

following we will describe the method we used to obtain such a set of

momenta for a configuration of separated reactants in water followed

by the simulation of the reactive pathway.

We started an AIMD simulation of the pentaaqua iron(II) hydrogen

peroxide complex in water, similar to the approach in the previous

section. As we now know, this complex is unstable against the iron(IV)

dihydroxo complex, so we constrained the H![]() O

O![]() oxygen-oxygen

bond distance to

oxygen-oxygen

bond distance to

![]() Å to prevent the

dissociation to occur. After an

equilibration time of 5 ps, we perturbed the system to force the

H

Å to prevent the

dissociation to occur. After an

equilibration time of 5 ps, we perturbed the system to force the

H![]() O

O![]() ligand to leave the complex and diffuse into the

solvent. There are several possibilities to make a ligand dissociate from

the complex, such as adding a potential

or changing the velocities of the iron complex and the H

ligand to leave the complex and diffuse into the

solvent. There are several possibilities to make a ligand dissociate from

the complex, such as adding a potential

or changing the velocities of the iron complex and the H![]() O

O![]() into

opposite directions. We, however, chose to shorten the Fe-O bond

distances for the five water ligands, which causes the complex to expel

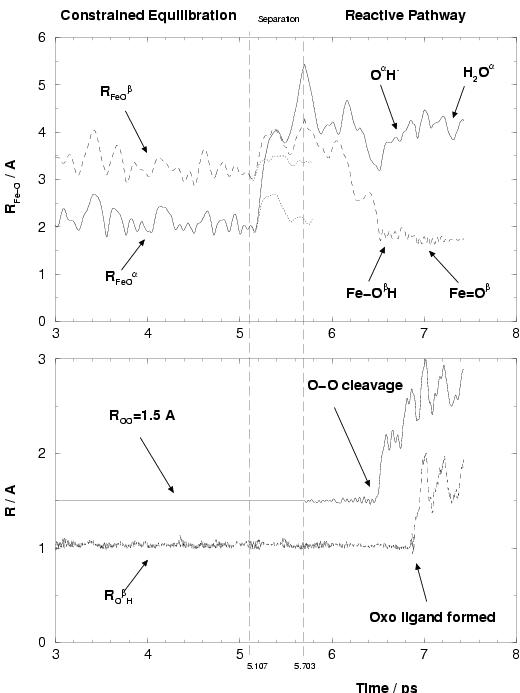

the hydrogen peroxide ligand. In figure 5.5, we

show the evolution of the two Fe-O (of Fe

into

opposite directions. We, however, chose to shorten the Fe-O bond

distances for the five water ligands, which causes the complex to expel

the hydrogen peroxide ligand. In figure 5.5, we

show the evolution of the two Fe-O (of Fe

![]() -H

-H![]() O

O![]() ) distances in the

upper graph, starting with the last two ps of the equilibration

phase. The lower graph shows the constrained O-O bond distance and the

HO

) distances in the

upper graph, starting with the last two ps of the equilibration

phase. The lower graph shows the constrained O-O bond distance and the

HO![]() distance, with

distance, with ![]() denoting the hydrogen peroxide

oxygen which is not bonded to iron (and

denoting the hydrogen peroxide

oxygen which is not bonded to iron (and ![]() denoting the other oxygen).

The shorter Fe-O

denoting the other oxygen).

The shorter Fe-O![]() distance

fluctuates around 2.11 Å which is slightly shorter than the average water

ligand Fe-O binding of 2.17 Å in this complex. We already expected

similar bonding properties for the H

distance

fluctuates around 2.11 Å which is slightly shorter than the average water

ligand Fe-O binding of 2.17 Å in this complex. We already expected

similar bonding properties for the H![]() O

O![]() and H

and H![]() O ligands from

the first bond dissociation energies in the gas phase complexes (see

table 5.2) being almost equal.

The hydrogen peroxide ligand is well solvated

by water molecules. Both hydrogens form hydrogen bonds to solvent water

molecules and also the oxygen O

O ligands from

the first bond dissociation energies in the gas phase complexes (see

table 5.2) being almost equal.

The hydrogen peroxide ligand is well solvated

by water molecules. Both hydrogens form hydrogen bonds to solvent water

molecules and also the oxygen O![]() accepts

on average 1 to 2 hydrogen bonds from solvent molecules.

accepts

on average 1 to 2 hydrogen bonds from solvent molecules.

|

At ![]() ps, we constrained the Fe-O distances of the

five water ligands at their actual value and shortened the bond length

in the following 100 steps (ca. 19.4 fs) to

ps, we constrained the Fe-O distances of the

five water ligands at their actual value and shortened the bond length

in the following 100 steps (ca. 19.4 fs) to ![]() Å. The result is that

the H

Å. The result is that

the H![]() O

O![]() ligand is expelled from the iron(II) coordination shell and moved

into the solvent, which is shown by the upper graph in figure

5.5. The dotted lines starting at

ligand is expelled from the iron(II) coordination shell and moved

into the solvent, which is shown by the upper graph in figure

5.5. The dotted lines starting at ![]() ps show

an unsuccessful attempt, where we shortened the five iron water

ligands distances to only

ps show

an unsuccessful attempt, where we shortened the five iron water

ligands distances to only ![]() Å. The solid and dashed lines,

however, show the successfully enforced dissociation, where especially

Å. The solid and dashed lines,

however, show the successfully enforced dissociation, where especially

![]() increases rapidly, within 600 fs, to a

distance of 5.4 Å. The other oxygen, O

increases rapidly, within 600 fs, to a

distance of 5.4 Å. The other oxygen, O![]() is hydrogen bonded to

2 solvent water molecules and also the hydrogen bonded to O

is hydrogen bonded to

2 solvent water molecules and also the hydrogen bonded to O![]() forms

a hydrogen bond to a solvent water, which makes this part of H

forms

a hydrogen bond to a solvent water, which makes this part of H![]() O

O![]() more

difficult to move and causes the H

more

difficult to move and causes the H![]() O

O![]() to rotate

during the separation, bringing

to rotate

during the separation, bringing ![]() furhter away from Fe than

furhter away from Fe than

![]() . At

. At ![]() ps, we now have a configuration of

separated reactants in water, with a set of momenta that will lead to

further separation. This configuration we take as the starting point

for our reaction pathway and we reverse all atomic velocities to

obtain a set of momenta that will lead to approaching reactants. Also,

the velocities of the fictitious plane wave coefficient dynamics are

reversed as well as the velocity of the Nosé thermostat variable.

We remove the H

ps, we now have a configuration of

separated reactants in water, with a set of momenta that will lead to

further separation. This configuration we take as the starting point

for our reaction pathway and we reverse all atomic velocities to

obtain a set of momenta that will lead to approaching reactants. Also,

the velocities of the fictitious plane wave coefficient dynamics are

reversed as well as the velocity of the Nosé thermostat variable.

We remove the H![]() O

O![]() oxygen-oxygen bond distance

constraint to allow dissociation to occur and also the five iron water

ligand bond distance constraints are removed. From this point we

start the simulation of the reaction pathway.

oxygen-oxygen bond distance

constraint to allow dissociation to occur and also the five iron water

ligand bond distance constraints are removed. From this point we

start the simulation of the reaction pathway.

The Verlet algorithm used for the integration of the equations of motion

is time reversible so that the system initially tracks back onto the ``forward''

trajectory of the separating reactants, when the velocities are reversed.

This can be seen from the symmetry of the

![]() plots in the upper graph (figure 5.5)

close to the mirror line at

plots in the upper graph (figure 5.5)

close to the mirror line at ![]() ps. However, due to the removal of

the bond distance constraints, the reversed trajectory diverges rapidly

from the forward path, as should be expected from the well-known Lyapunov

instability of MD trajectories towards small differences in the initial

conditions. In fact, the trajectory followed by the approaching reactants is so

much different from the trajectory followed by the separating reactants that

now the other H

ps. However, due to the removal of

the bond distance constraints, the reversed trajectory diverges rapidly

from the forward path, as should be expected from the well-known Lyapunov

instability of MD trajectories towards small differences in the initial

conditions. In fact, the trajectory followed by the approaching reactants is so

much different from the trajectory followed by the separating reactants that

now the other H![]() O

O![]() oxygen O

oxygen O![]() forms a bond with

the iron(II) complex at

forms a bond with

the iron(II) complex at ![]() ps, i.e. 0.8 ps after the

velocities were reversed.

Almost immediately after the Fe-O

ps, i.e. 0.8 ps after the

velocities were reversed.

Almost immediately after the Fe-O![]() bond is formed the H

bond is formed the H![]() O

O![]() dissociates, which can be seen from the increasing

dissociates, which can be seen from the increasing

![]() and

and

![]() after

after ![]() ps in figure 5.5.

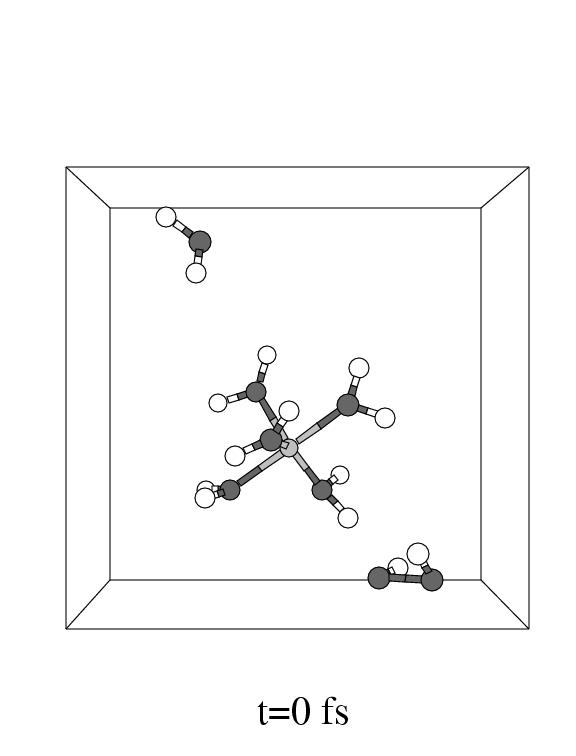

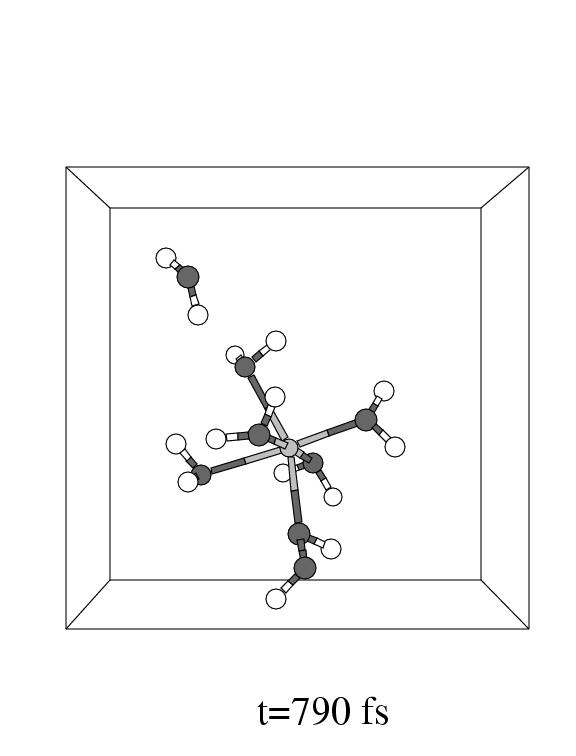

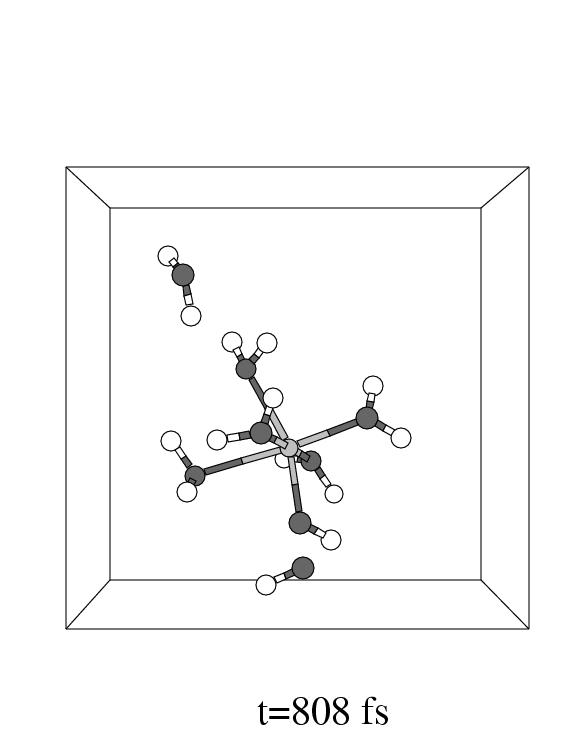

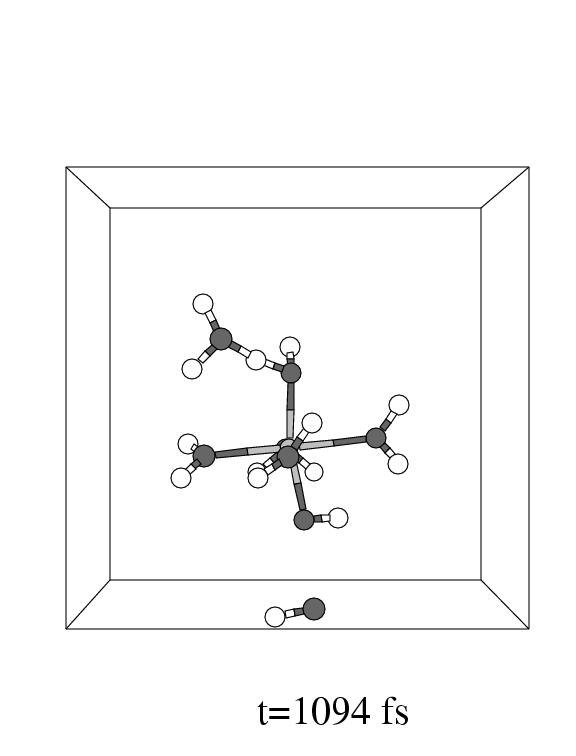

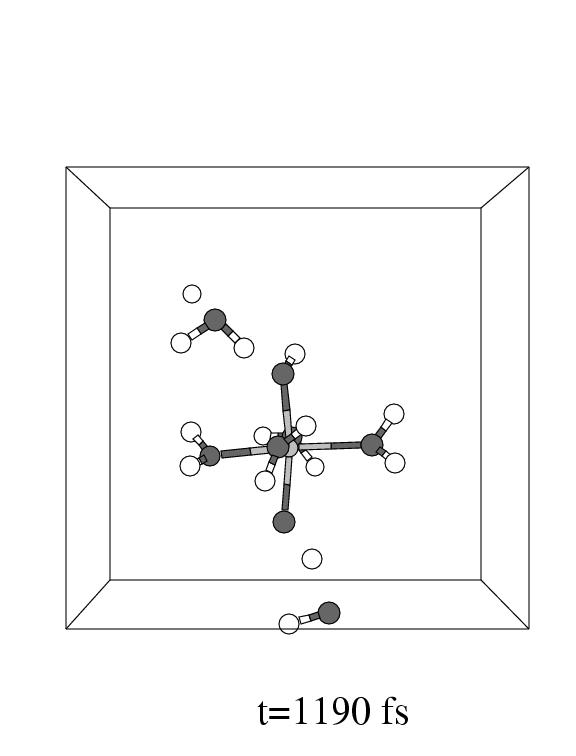

The first three pictures in figure 5.6 show snapshots

of the system (with omission of all solvent water molecules, except one, for

clarity) during this coordination process.

Note that the incoming hydrogen peroxide, in the lower part of the unit cell

in panel 1, to the right, enters the vacant coordination site of the pentaaqua

Fe(II) complex in panel 2. Apparently, the incoming hydrogen peroxide does not

equilibrate in the local minimum representing the iron hydrogen peroxide complex,

but instead it dissociates as soon as the iron oxygen distance reaches the short

value of 2.1 Å forming the (formally) Fe

ps in figure 5.5.

The first three pictures in figure 5.6 show snapshots

of the system (with omission of all solvent water molecules, except one, for

clarity) during this coordination process.

Note that the incoming hydrogen peroxide, in the lower part of the unit cell

in panel 1, to the right, enters the vacant coordination site of the pentaaqua

Fe(II) complex in panel 2. Apparently, the incoming hydrogen peroxide does not

equilibrate in the local minimum representing the iron hydrogen peroxide complex,

but instead it dissociates as soon as the iron oxygen distance reaches the short

value of 2.1 Å forming the (formally) Fe![]() -OH

-OH![]() complex

and a hydroxyl radical.

The much shorter average iron hydroxo ligand bond

length of

complex

and a hydroxyl radical.

The much shorter average iron hydroxo ligand bond

length of

![]() Å and the higher frequency compared

to the Fe-O bond of a H

Å and the higher frequency compared

to the Fe-O bond of a H![]() O

O![]() or H

or H![]() O ligand confirm that indeed the

O

O ligand confirm that indeed the

O![]() H. brought

the iron to the higher oxidation state of +3, increasing the bond strength by

the extra electrostatic attraction. About 350 fs after the O

H. brought

the iron to the higher oxidation state of +3, increasing the bond strength by

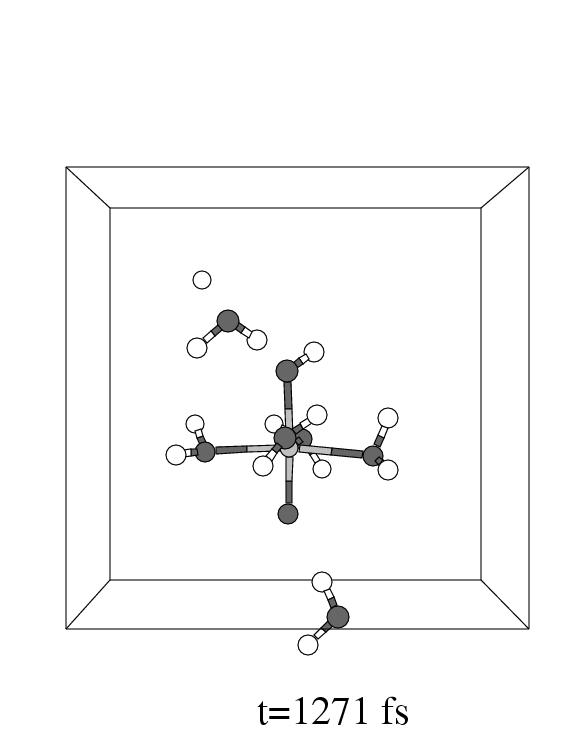

the extra electrostatic attraction. About 350 fs after the O![]() H.

radical is formed, it is attracted by the hydrogen of the O

H.

radical is formed, it is attracted by the hydrogen of the O![]() H

H![]() hydroxo ligand, which is abstracted about

50 fs later to form a water molecule and the ferryl ion moiety.

The average Fe

hydroxo ligand, which is abstracted about

50 fs later to form a water molecule and the ferryl ion moiety.

The average Fe![]() =O

=O![]() bond length of 1.72 Å is even shorter than

the iron-oxygen bond in the Fe

bond length of 1.72 Å is even shorter than

the iron-oxygen bond in the Fe![]() -OH

-OH![]() complex (see again

figure 5.5) and also the frequency increases

with 100-200 cm

complex (see again

figure 5.5) and also the frequency increases

with 100-200 cm![]() to roughly 700 cm

to roughly 700 cm![]() (the statistics do not allow

for an accurate number for the frequency).

Again, we have found the spontaneous formation of the ferryl ion.

(the statistics do not allow

for an accurate number for the frequency).

Again, we have found the spontaneous formation of the ferryl ion.

|

One of the side effects of the increasing oxidation state of the iron complex, going

from 2+ to 4+ during the reactive pathway, is that the acidity of the complex

increases. We have already seen this phenomenon in the simulation described in the

previous section. Again, as shown in the last three snapshots in figure

5.6, hydrolysis of one water ligand takes place at a

time somewhere between the moment that the Fe

![]() complex was

formed and the momemt that Fe

complex was

formed and the momemt that Fe

![]() was formed.

So also in this reactive pathway we end up with the [(H

was formed.

So also in this reactive pathway we end up with the [(H![]() O)

O)![]() Fe(IV)(OH)(O)]

Fe(IV)(OH)(O)]![]() complex and an extra proton in the solvent.

complex and an extra proton in the solvent.

Although the same iron(IV)oxo complex is formed as in the previous

simulations starting from the equilibrated pentaaqua iron(II) hydrogen

peroxide complex, there is a difference in the mechanism.

In the previous sections, we have seen the formation of the dihydroxo iron(IV)

complex as the initial step, as was also predicted by our gas phase study.

The iron(IV)oxo complex (ferryl ion) can then be formed in a second step

by hydrolysis of an hydroxo ligand

(as demonstrated by our first simulation, section 5.3.2).

Instead, in the present simulation starting from separated reactants,

the ferryl ion is formed via a more direct mechanism. The OH. radical

does not find a fast terminating route along an H-bond wire to a water ligand to form a

dihydroxo complex, but stays in the neighborhood of the formed

OH![]() ligand and then finds a quenching pathway by abstracting its hydrogen

after roughly 0.3 ps.

Apparently, in this case, a pathway to quench the radical in concertation with

the O-O bond cleavage and make the process exothermic is not necessary.

Indeed, in the present simulation, the energy balance is different.

Starting from coordinated H

ligand and then finds a quenching pathway by abstracting its hydrogen

after roughly 0.3 ps.

Apparently, in this case, a pathway to quench the radical in concertation with

the O-O bond cleavage and make the process exothermic is not necessary.

Indeed, in the present simulation, the energy balance is different.

Starting from coordinated H![]() O

O![]() (section 5.3.2) the energy

needed for the OH. formation is equal to the energy needed to dissociate

the oxygen-oxygen bond of H

(section 5.3.2) the energy

needed for the OH. formation is equal to the energy needed to dissociate

the oxygen-oxygen bond of H![]() O

O![]() (A in table 5.2)

minus the energy gain of replacing the Fe

(A in table 5.2)

minus the energy gain of replacing the Fe

![]() -H

-H![]() O

O![]() bond

with the much stronger Fe

bond

with the much stronger Fe

![]() -OH bond (C-D).

Starting with a vacant coordination site and H

-OH bond (C-D).

Starting with a vacant coordination site and H![]() O

O![]() in solvation (the

present simulation) leaves us with an extra 23 kcal/mol (neglecting the solvent

effects), which is enough to form the OH. radical without the

need of a fast transfer to an exothermic termination.

in solvation (the

present simulation) leaves us with an extra 23 kcal/mol (neglecting the solvent

effects), which is enough to form the OH. radical without the

need of a fast transfer to an exothermic termination.

The reactive pathways presented in this work illustrate possible

microscopic routes via which the chemical reactions could take place.

In a next study, will test how realistic the last pathway, illustrating

coordination and reaction of H![]() O

O![]() with iron(II), is, by initiating

many new reactive trajectories from this last pathway using the method

of transition path sampling.

with iron(II), is, by initiating

many new reactive trajectories from this last pathway using the method

of transition path sampling.