Starting from hydrogen peroxide coordinated to Fe

The system of H![]() O

O![]() coordinated to Fe

coordinated to Fe![]() in water was created

from a previous CP-PAW MD run of Fe

in water was created

from a previous CP-PAW MD run of Fe![]() (high spin)

in a periodic cubic unit cell with 32 water molecules,

by replacing one of the six water ligands by hydrogen

peroxide. A short MD run of 1.16 ps. averaged out the short memory of any unphysical

forces or velocities arising from the construction of the system.

The pentaaqua iron(II) hydrogen peroxide complex was found to be

a local minumum on the potential energy surface in the gas phase[145]

and has also been proposed as a stable intermediate in aqueous

solution[167,176]. As we however found that the barrier

for oxygen-oxygen lysis in water is very small, we fixed the hydrogen

peroxide oxygen-oxygen distance at

(high spin)

in a periodic cubic unit cell with 32 water molecules,

by replacing one of the six water ligands by hydrogen

peroxide. A short MD run of 1.16 ps. averaged out the short memory of any unphysical

forces or velocities arising from the construction of the system.

The pentaaqua iron(II) hydrogen peroxide complex was found to be

a local minumum on the potential energy surface in the gas phase[145]

and has also been proposed as a stable intermediate in aqueous

solution[167,176]. As we however found that the barrier

for oxygen-oxygen lysis in water is very small, we fixed the hydrogen

peroxide oxygen-oxygen distance at

![]() Å and the

Fe-H

Å and the

Fe-H![]() O

O![]() distance at

distance at

![]() Å, during this period of

system equilibration, to prevent the premature breakup of the complex by

the unrelaxed environment.

Also the five iron-water ligand distances

Å, during this period of

system equilibration, to prevent the premature breakup of the complex by

the unrelaxed environment.

Also the five iron-water ligand distances ![]() (FeO) were constrained the

first 0.65 ps to their value at the first time step

(

(FeO) were constrained the

first 0.65 ps to their value at the first time step

(

![]() Å).

Å).

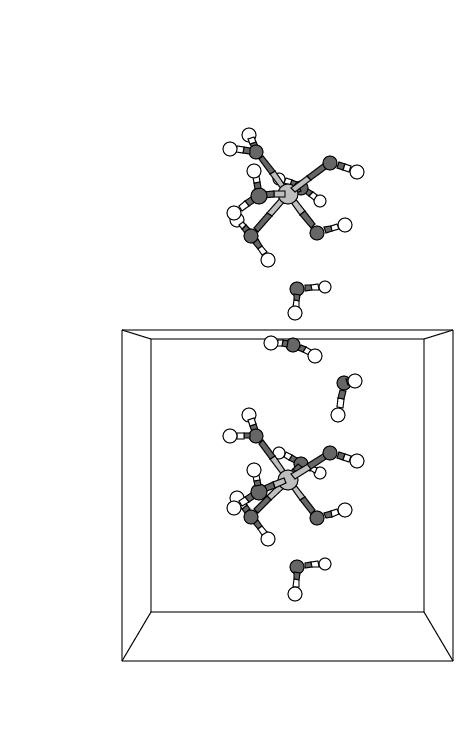

After the equilibration, the MD simulation was continued (without

any bond constraints) and the evolution of the coordinated Fenton

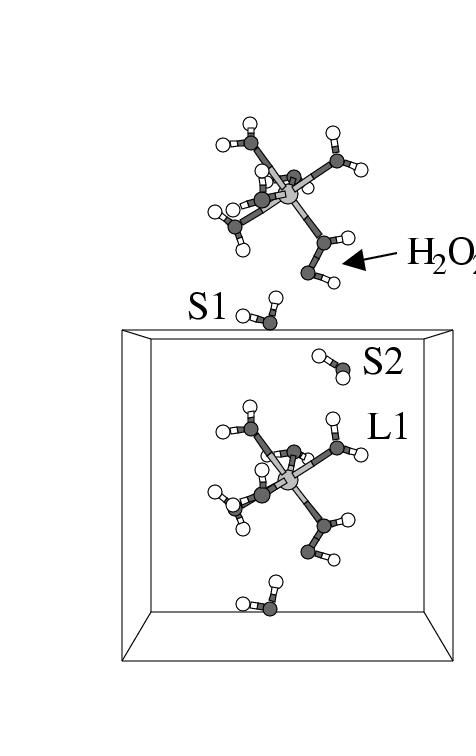

reagent in water was followed for 10.2 ps. Figure 5.3

shows five snapshots of the [(H![]() O)

O)![]() Fe

Fe

![]() (H

(H![]() O

O![]() )]

)]![]() complex

in the cubic unit cell at subsequent times during the first part of the

simulation. Two of the solvent molecules have also been drawn, since they

take part in the reaction to be described below; all other solvent molecules

have been left out for clarity. The cubic unit cell is surrounded at all sides

by its periodic repetitions, which provides a representation of the infinite

solvent environment. In order to aid the discussion, we have drawn in figure

5.3 one periodic repetition of the complex and one water

molecule in the cell above the central unit cell. Note that this water molecule

is the periodic repetition of the water molecule drawn close to the bottom of

the central unit cell. It is interesting to observe that in the first panel

the orientations of the H

complex

in the cubic unit cell at subsequent times during the first part of the

simulation. Two of the solvent molecules have also been drawn, since they

take part in the reaction to be described below; all other solvent molecules

have been left out for clarity. The cubic unit cell is surrounded at all sides

by its periodic repetitions, which provides a representation of the infinite

solvent environment. In order to aid the discussion, we have drawn in figure

5.3 one periodic repetition of the complex and one water

molecule in the cell above the central unit cell. Note that this water molecule

is the periodic repetition of the water molecule drawn close to the bottom of

the central unit cell. It is interesting to observe that in the first panel

the orientations of the H![]() O

O![]() ligand at the top iron complex, the water at the

bottom in the top cell (indicated with ``S1''), and the water in the upper part of

the central cell (``S2'') together with a water ligand at the Fe in the central

cell (``L1'') are close to creating an H-bond wire.

This H-bond wire is fully established in the second panel by slight

reorientations of the water molecules.

ligand at the top iron complex, the water at the

bottom in the top cell (indicated with ``S1''), and the water in the upper part of

the central cell (``S2'') together with a water ligand at the Fe in the central

cell (``L1'') are close to creating an H-bond wire.

This H-bond wire is fully established in the second panel by slight

reorientations of the water molecules.

|

Almost immediately after the bond constraints were released at t=0 fs, the peroxide

dissociates into a hydroxo group coordinated to iron and an OH. radical

which attacks a solvent water molecule that was hydrogen bonded to the hydrogen

peroxide ![]() -oxygen

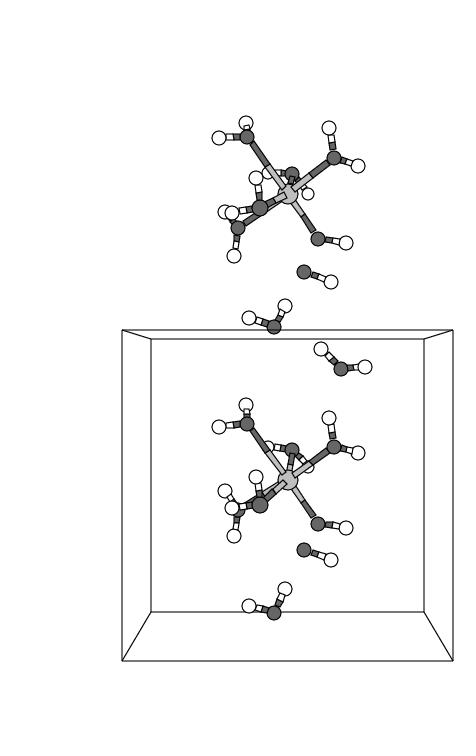

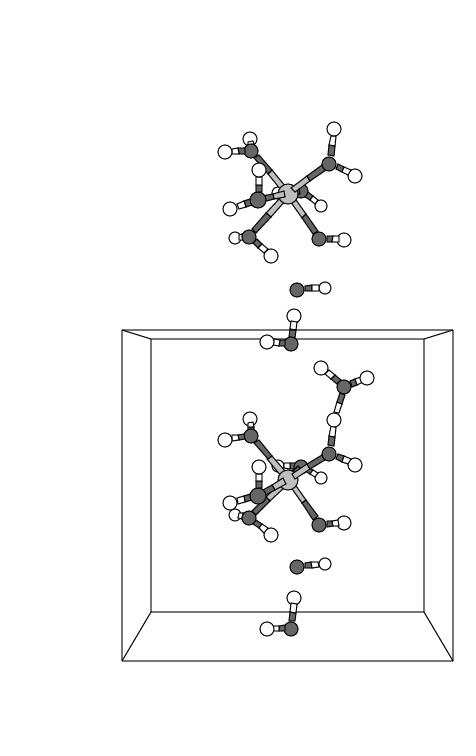

(see snapshots 1 and 2 in figure 5.3). Snapshots 2 and 3

show this solvent water molecule (the water molecule in the lower part of the

central unit cell, as well as its periodic image drawn in the top cell) moving

to the cell boundary, and in panel 4 actually crossing the boundary (at least an

OH moiety). This OH moiety leaves the central unit cell across the bottom plane,

but of course the periodic image OH in the top cell leaves the top cell and enters

the central unit cell across the top plane of the central cell. The H of this

H

-oxygen

(see snapshots 1 and 2 in figure 5.3). Snapshots 2 and 3

show this solvent water molecule (the water molecule in the lower part of the

central unit cell, as well as its periodic image drawn in the top cell) moving

to the cell boundary, and in panel 4 actually crossing the boundary (at least an

OH moiety). This OH moiety leaves the central unit cell across the bottom plane,

but of course the periodic image OH in the top cell leaves the top cell and enters

the central unit cell across the top plane of the central cell. The H of this

H![]() O is abstracted by the OH. radical coming from the coordinated

H

O is abstracted by the OH. radical coming from the coordinated

H![]() O

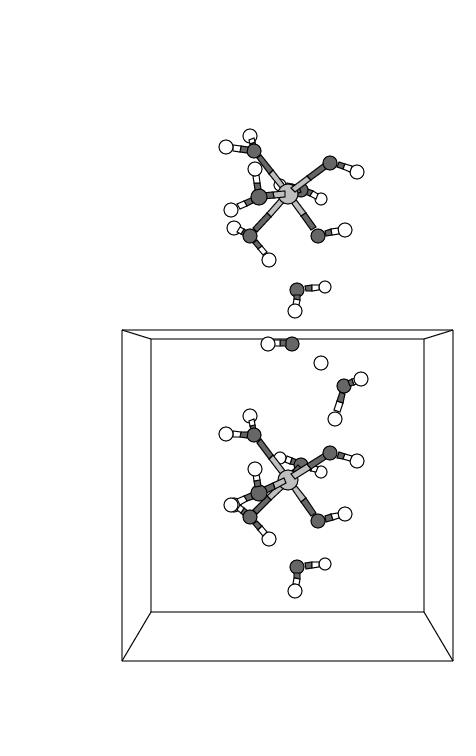

O![]() . The intertesting point (see snapshots 4 and 5) is that the OH.

radical through a chain of H abstractions, running along the preestablished H-bond

wire, actually abstracts a H from a water ligand of the neigbouring Fe complex.

Closer inspection shows that the radical passage is not a typical chain reaction but

rather a concerted process: snapshot 3 reveals that the "chain"

starts simultaneously at both ends and is terminated in the middle (snapshot 4 and 5).

. The intertesting point (see snapshots 4 and 5) is that the OH.

radical through a chain of H abstractions, running along the preestablished H-bond

wire, actually abstracts a H from a water ligand of the neigbouring Fe complex.

Closer inspection shows that the radical passage is not a typical chain reaction but

rather a concerted process: snapshot 3 reveals that the "chain"

starts simultaneously at both ends and is terminated in the middle (snapshot 4 and 5).

The formation of the tetraaqua iron(IV) dihydroxo complex as the first step in the

H![]() O

O![]() dissociation (eq. 5.3) agrees with the energetic

requirements derived from the gas phase calculations, see section 5.3.1.

Of course, the concerted radical passage could not be observed without explicit

inclusion of the aqueous solvent environment. The use of periodic boundary conditions

is a means to simulate the "infinite" solvent environment with finite computational

resources. It is, however, from this simulation easy to see what the possibilities

are in a very large cell, or in a system without periodicity. We have established

that O-O dissociation in a coordinated H

dissociation (eq. 5.3) agrees with the energetic

requirements derived from the gas phase calculations, see section 5.3.1.

Of course, the concerted radical passage could not be observed without explicit

inclusion of the aqueous solvent environment. The use of periodic boundary conditions

is a means to simulate the "infinite" solvent environment with finite computational

resources. It is, however, from this simulation easy to see what the possibilities

are in a very large cell, or in a system without periodicity. We have established

that O-O dissociation in a coordinated H![]() O

O![]() , leading to one Fe-OH bond and an

OH. radical, is only energetically possible if an additional Fe-OH bond is formed.

This implies that the concerted radical path has to terminate at a water ligand.

This leaves the following possibilities:

a) if the pentaaqua iron(II) hydrogen peroxide complex would be in the neighborhood

of a hexaaqua iron(II) complex, the OH.

passage might be, via two or three solvent waters, to a water ligand of the

hexaaqua iron(II), with two mono-hydroxo pentaaqua iron(III) complexes as the result;

b) with only one pentaaqua iron(II) hydrogen

peroxide complex in such a system, the radical passage

can go via a few solvent waters and end up with hydrogen

abstraction from one of the water ligands of this same iron complex, resulting in the

dihydroxo complex.

This is the likely reaction pathway in a typical experimental situation

where the iron catalyst is present in a low concentration.

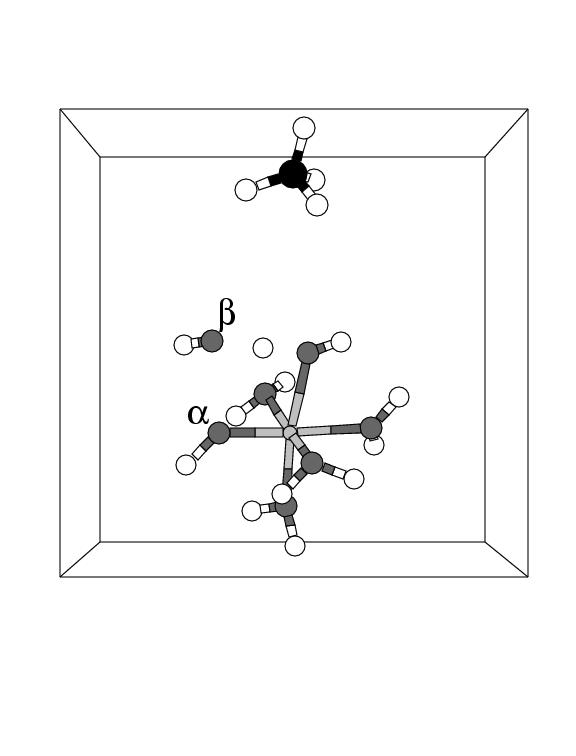

Indeed, in preliminary simulations we are performing to study the possibility of H

abstraction from organic substrates, we have encountered reaction pathways

in which the H abstraction took place from H

, leading to one Fe-OH bond and an

OH. radical, is only energetically possible if an additional Fe-OH bond is formed.

This implies that the concerted radical path has to terminate at a water ligand.

This leaves the following possibilities:

a) if the pentaaqua iron(II) hydrogen peroxide complex would be in the neighborhood

of a hexaaqua iron(II) complex, the OH.

passage might be, via two or three solvent waters, to a water ligand of the

hexaaqua iron(II), with two mono-hydroxo pentaaqua iron(III) complexes as the result;

b) with only one pentaaqua iron(II) hydrogen

peroxide complex in such a system, the radical passage

can go via a few solvent waters and end up with hydrogen

abstraction from one of the water ligands of this same iron complex, resulting in the

dihydroxo complex.

This is the likely reaction pathway in a typical experimental situation

where the iron catalyst is present in a low concentration.

Indeed, in preliminary simulations we are performing to study the possibility of H

abstraction from organic substrates, we have encountered reaction pathways

in which the H abstraction took place from H![]() O coordinated to the same Fe

center (see figure 5.4).

O coordinated to the same Fe

center (see figure 5.4).

|

We observed that the formed iron(IV)dihydroxo complex is in equilibrium with its conjugate base by proton donation to the solvent (eq 5.4).

The apparent acidity of the Fe

![]() complex obviously can only be seen in a simulation including the solvent. The donated proton is passed on in the solvent to end up again on

a hydroxo ligand, which

of course does not have to be the same ligand that donated the proton to the

solvent initially. Then, hydrolysis of this newly formed or another water

ligand may take

place, and so forth. As a result of this dynamic equilibrium, the hydroxo ligands

are transformed into water ligands and vice versa.

Eventually at a time when the system happens to find itself on the

left-hand-side of equation 5.4

(in our simulation, 1.7 ps after the formation of the dihydroxo iron(IV)

complex, eq. 5.3),

a proton is donated by a hydroxo ligand instead of

a water ligand and the iron-oxo complex is formed in our simulation.

complex obviously can only be seen in a simulation including the solvent. The donated proton is passed on in the solvent to end up again on

a hydroxo ligand, which

of course does not have to be the same ligand that donated the proton to the

solvent initially. Then, hydrolysis of this newly formed or another water

ligand may take

place, and so forth. As a result of this dynamic equilibrium, the hydroxo ligands

are transformed into water ligands and vice versa.

Eventually at a time when the system happens to find itself on the

left-hand-side of equation 5.4

(in our simulation, 1.7 ps after the formation of the dihydroxo iron(IV)

complex, eq. 5.3),

a proton is donated by a hydroxo ligand instead of

a water ligand and the iron-oxo complex is formed in our simulation.

Such proton donation by a hydroxo ligand has been reported before for

e.g. the mechanism for oxo-hydroxo tautomerism observed by high-valent

iron porphyrins with an oxo and hydroxo group as axial ligands in aqueous

solution.[177]

After another two pico-seconds, one of the water ligands

leaves the first solvation shell[178], and the formed

![$\left[(\mathrm{H}_2\mathrm{O})_3\mathrm{Fe^{IV}O}(\mathrm{OH})\right]^{+}$](img558.png) complex undergoes no more spontaneous chemical changes in the next 6

pico-seconds.

complex undergoes no more spontaneous chemical changes in the next 6

pico-seconds.

The reported reaction pathway took place spontaneously, once we had

constructed the initial reactants configuration.

The observed reactions occur apparently without a significant reaction barrier,

which puts doubt on the assumption in certain kinetic

models[167,176] that there exists a steady state of the

concentration of complexed [Fe![]() -H

-H![]() O

O![]() ]

]![]() .

In agreement with the energetics obtained in gas phase calculations,

we confirm the formation of the iron(IV)-oxo complex from the Fenton reagent,

but in view of the ``radical passage'' mechanism

of the first step (figure 5.3), the question may be raised

whether OH. radicals can be excluded as possible reactive intermediates.

In the gas phase, we find that reaction 5.6

.

In agreement with the energetics obtained in gas phase calculations,

we confirm the formation of the iron(IV)-oxo complex from the Fenton reagent,

but in view of the ``radical passage'' mechanism

of the first step (figure 5.3), the question may be raised

whether OH. radicals can be excluded as possible reactive intermediates.

In the gas phase, we find that reaction 5.6

is endothermic by 21 kcal/mol (table 5.2).

The OH. formation followed by transfer away from the complex into the

solvent, where it might react further with an organic substrate, is therefore

not likely. Instead, the radical is quenched, according to the pathway in

figure 5.3, through a short, energetically favorable,

transfer along a hydrogen-bond wire through the solvent to a complex

(either the initial one or a neighboring complex) where

the necessary energy is gained by formation of a second OH ligand.

Only in case of a high organic substrate concentration, i.e. a high chance

of finding an organic molecule in the neighborhood of the iron complex where the

hydrogen peroxide is coordinated, can we expect the OH. radical

to have a significant contribution in the oxidation reactions, because the radical

transfer could find a path along an H-bond wire to an organic substrate molecule

if the latter is close enough.

In all other cases, the ferryl ion is expected to be the active intermediate

formed by the Fe

![]() and hydrogen peroxide in water.

and hydrogen peroxide in water.

The quenching of the OH. radical by hydrogen abstraction from a H![]() O

ligand explains a

notorious problem in the application of the Fenton reagent, namely the

degradation of the chelating agents

(see e.g. refs. RaRi88,RuKo87,TaRoBo99).

Chelating agents are bulky ligand complexes, applied to

increase the solubility of the iron catalyst. However, in practice the

ligands degrade during the reaction, reducing the number of catalytic

cycles per metal complex. The degradation can now be understood as the

scavenging process by the very short-lived OH. radical, which is initially

formed in the H

O

ligand explains a

notorious problem in the application of the Fenton reagent, namely the

degradation of the chelating agents

(see e.g. refs. RaRi88,RuKo87,TaRoBo99).

Chelating agents are bulky ligand complexes, applied to

increase the solubility of the iron catalyst. However, in practice the

ligands degrade during the reaction, reducing the number of catalytic

cycles per metal complex. The degradation can now be understood as the

scavenging process by the very short-lived OH. radical, which is initially

formed in the H![]() O

O![]() oxygen-oxygen cleavage.

oxygen-oxygen cleavage.