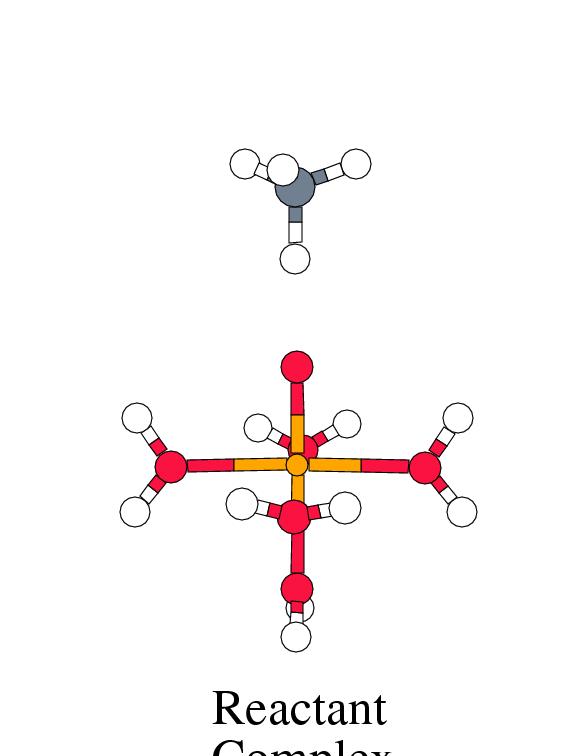

In this section, we present the results for the methane-to-methanol

oxidation by the aqua iron(IV)oxo species, following the oxygen-rebound

mechanism. This mechanism consists of two steps: first the hydrogen abstraction

from methane by the iron(IV)oxo species, producing iron(III)hydroxo and

a .CH![]() radical, and second, the collapse of the .CH

radical, and second, the collapse of the .CH![]() radical

onto the iron(III)hydroxo oxygen, forming Fe(II)CH

radical

onto the iron(III)hydroxo oxygen, forming Fe(II)CH![]() OH.

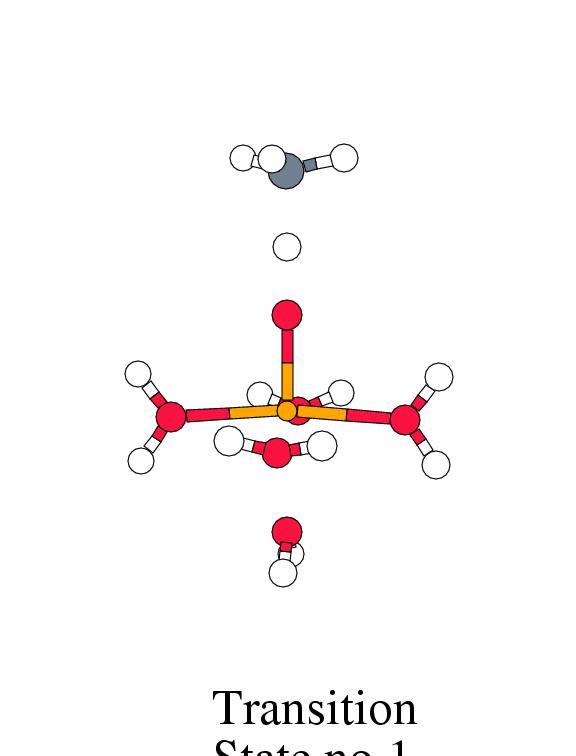

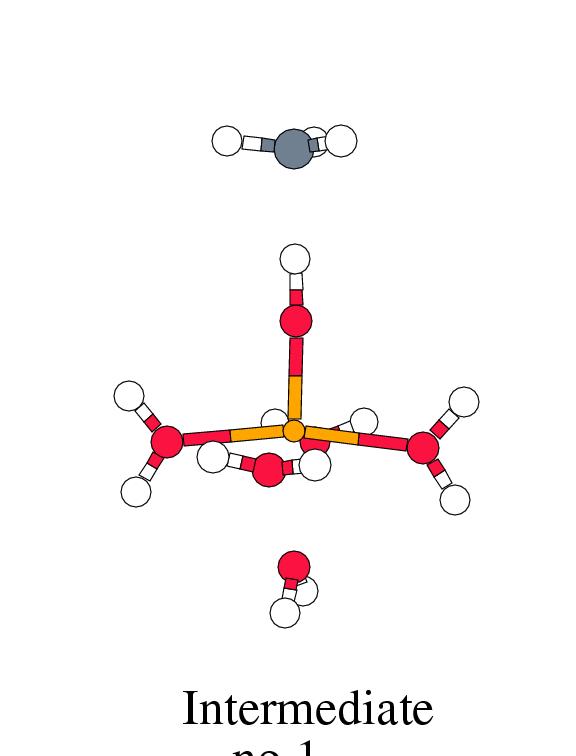

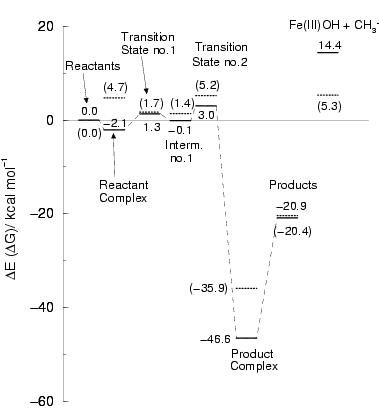

Figure 8.2 shows the energy profile for

these reaction steps along with the intermediate complex geometries.

For this mechanism, we have also computed the zero-point energy corrections, the

temperature dependent enthalpy corrections for a temperature of

OH.

Figure 8.2 shows the energy profile for

these reaction steps along with the intermediate complex geometries.

For this mechanism, we have also computed the zero-point energy corrections, the

temperature dependent enthalpy corrections for a temperature of ![]() K

and the entropy term

K

and the entropy term ![]() (see table 8.3),

the sum of which is added to the internal energy to give the

free energy, indicated in figure 8.2 between

parentheses.

(see table 8.3),

the sum of which is added to the internal energy to give the

free energy, indicated in figure 8.2 between

parentheses.

[width=77mm]

|

|

|

|||||||

| Reactant | Trans. | Inter- | Free | Trans. | Product | Free | |

| Complex | State 1 | mediate | Radic. | State 2 | Complex | Products | |

|

|

|||||||

|

Fenton |

-2.1 | 1.3 | -0.1 | 14.4 | 3.0 | -46.6 | -20.9 |

|

MMO |

2.3 | 13.8 | 2.8 | 7.6 | -47.7 | ||

|

MMO |

-1.5 | 23.2 | 11.3 | 23.7 | 20.6 | -41.8 | -34.3 |

|

P450 |

-1.0 | 26.7 | 23.6 | 29.1 | -36.9 | ||

|

|

|||||||

|

|

-0.8 | -4.9 | -3.3 | -3.9 | -3.5 | 1.8 | 0.1 |

|

|

0.4 | -4.4 | -1.7 | -1.8 | -2.1 | 4.2 | -1.3 |

|

|

7.2 | 9.7 | 6.6 | -3.4 | 7.8 | 4.6 | 1.7 |

|

|

||||||||

| Free | React. | Trans. | Inter- | Free | Trans. | Prod. | Free | |

| React. | Comp. | State 1 | mediate | Radic. | State 2 | Comp. | Prod. | |

|

|

||||||||

|

|

1.61 | 1.63 | 1.72 | 1.77 | 1.77 | 1.79 | 2.09 | |

|

|

2.91 | 2.55 | 2.78 | 2.50 | 1.47 | |||

|

|

1.76 | 1.20 | 1.03 | 0.98 | 1.01 | 0.97 | 1.43 | |

|

|

1.10 | 1.15 | 1.34 | 1.76 | 1.70 | 1.99 | 0.97 | |

|

|

1. | 0. | 1. | 30. | 108. | 108. | ||

|

|

179. | 176. | 155. | 179. | 151. | 120. | ||

|

|

||||||||

|

|

1.35 | 1.36 | 1.46 | 1.43 | 1.49 | 1.43 | 1.30 | 1.33 |

|

|

-0.20 | -0.30 | -0.48 | -0.36 | -0.25 | -0.37 | -0.08 | -0.09 |

|

|

0.30 | 0.34 | 0.34 | 0.30 | 0.00 | 0.33 | 0.30 | 0.22 |

|

|

0.08 | 0.13 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.00 | 0.34 | 0.21 | 0.02 |

|

|

-0.08 | -0.11 | 0.04 | -0.03 | 0.07 | -0.02 | 0.05 | 0.07 |

|

|

||||||||

|

|

3.14 | 3.40 | 3.97 | 4.11 | 4.20 | 4.08 | 3.83 | 3.85 |

|

|

0.69 | 0.59 | 0.38 | 0.40 | 0.52 | 0.35 | 0.04 | 0.00 |

|

|

0.00 | -0.10 | -0.50 | -0.75 | 1.08 | -0.65 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

|

|

0.00 | -0.04 | -0.03 | -0.01 | 0.03 | -0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

|

The interaction between the methane substrate and the iron(IV)oxo complex

is again very weak, equal to ![]() 2 kcal/mol. The first reaction step, the

transfer of a CH

2 kcal/mol. The first reaction step, the

transfer of a CH![]() hydrogen from methane to the oxo ligand, forming an

Fe(III)OH complex with a bound .CH

hydrogen from methane to the oxo ligand, forming an

Fe(III)OH complex with a bound .CH![]() radical, is surprisingly easy.

The overall reaction energy is

radical, is surprisingly easy.

The overall reaction energy is ![]() kcal/mol, and the barrier is only

3.4 kcal/mol (1.3 kcal/mol with respect to the free reactants).

Release of the .CH

kcal/mol, and the barrier is only

3.4 kcal/mol (1.3 kcal/mol with respect to the free reactants).

Release of the .CH![]() group, producing a free radical,

was calculated from the energy difference of the separate geometry

optimized structures to cost 14.4 kcal/mol. In contrast to H-abstraction

from an isolated CH

group, producing a free radical,

was calculated from the energy difference of the separate geometry

optimized structures to cost 14.4 kcal/mol. In contrast to H-abstraction

from an isolated CH![]() molecule which costs 103 kcal/mol

(calculated at the DFT-BP+ZPE level of theory), the energy surface is very

flat due to the simultaneous formation of the OH bond with the breaking

of the CH bond. Also compared to the formation of the free .CH

molecule which costs 103 kcal/mol

(calculated at the DFT-BP+ZPE level of theory), the energy surface is very

flat due to the simultaneous formation of the OH bond with the breaking

of the CH bond. Also compared to the formation of the free .CH![]() radical

from the reactant complex, which costs 16.5 kcal/mol, the reaction

energy needed to go from Fe(IV)O

radical

from the reactant complex, which costs 16.5 kcal/mol, the reaction

energy needed to go from Fe(IV)O![]() HCH

HCH![]() to Fe(III)OH

to Fe(III)OH![]() CH

CH![]() is very small. This is obviously due to fairly strong (14.5 kcal/mol) bond between

the .CH

is very small. This is obviously due to fairly strong (14.5 kcal/mol) bond between

the .CH![]() radical and the Fe(III)OH complex. We have not analyzed this

bond in detail, but we note that there is a significant charge transfer contribution

from CH

radical and the Fe(III)OH complex. We have not analyzed this

bond in detail, but we note that there is a significant charge transfer contribution

from CH![]() to the iron complex concomitant with the H-abstraction

(see also the substantial absolute increase of

to the iron complex concomitant with the H-abstraction

(see also the substantial absolute increase of ![]() O and

O and ![]() CH

CH![]() as

as ![]() OH decreases

and

OH decreases

and ![]() CH increases in table 8.4, whereas the charge

on CH

CH increases in table 8.4, whereas the charge

on CH![]() becomes zero for the free radical formation).

becomes zero for the free radical formation).

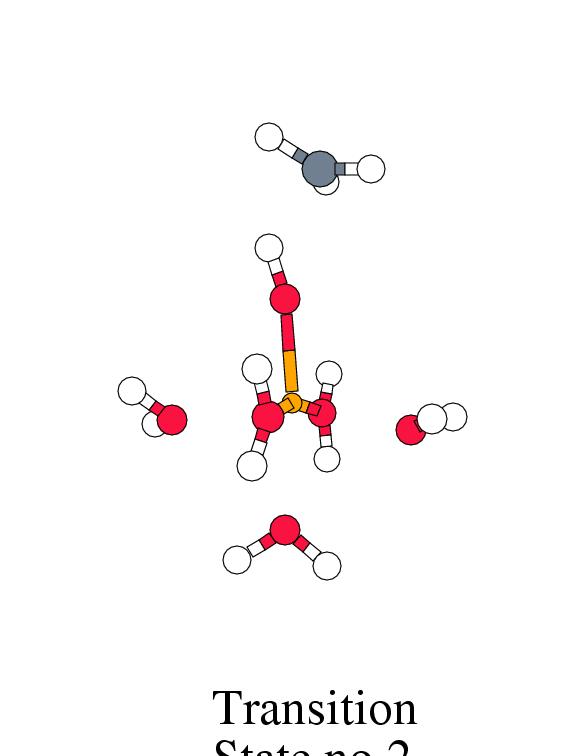

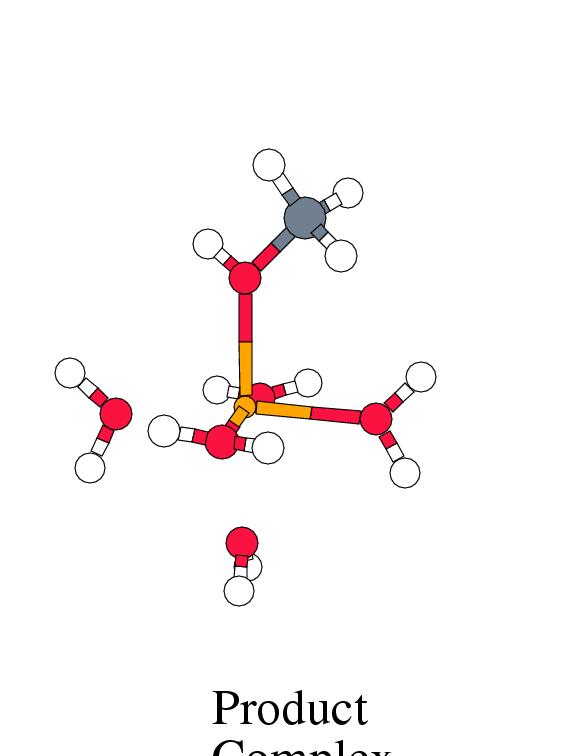

For the second step in the oxygen-rebound mechanism,

we find the formation of methanol bound to pentaaqua iron(II) to be very

exothermic (46.6 kcal/mol), with again a very small barrier,

equal to 3.1 kcal/mol. We did not

succeed in finding this second transition state from geometry optimization

along the unstable mode of the Hessian, due to convergence problems

(which is a notorious problem of weakly bound radicals to transition

metal complexes, see e.g. ref. Si01). However, from the

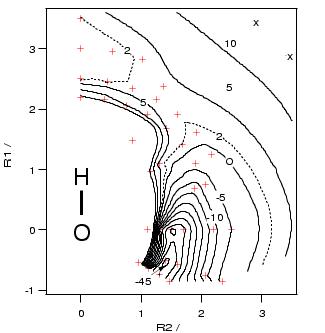

potential energy surface shown in figure 8.3, we could

determine the transition state structure to be the one shown in

figure 8.2. This potential energy surface

was computed from a geometry optimization for each point (indicated

by the crosses) constraining only the C-O bond distance and the H-O-C

angle. The oxygen of the hydroxo complex is situated at the coordinates

(0,0) in the plot and the ![]() axis is depicted to be along O-H.

The energy of the Fe

axis is depicted to be along O-H.

The energy of the Fe![]() -OH

-OH![]() CH

CH![]() intermediate, which is a local minimum on the energy surface,

was set to zero in figure 8.2

The potential energy surface shows that there exists a

narrow channel, through which the bound methyl radical can rotate around the

hydroxo hydrogen to bind with the oxygen. The channel is very flat up to an

H-O-C angle of about 60 degrees, with a small maximum at an angle of

30 degrees (transition state no.2), but then enters a very steep well

associated with the irreversible formation of methanol. From the

zero-Kelvin energy, this second step seems thus much more likely than

formation of the free methyl radical.

However, if we include zero-point energy effects, temperature corrections

and entropy effects, we see that the free energy barriers are similar,

namely 5.2 and 5.3 kcal/mol, respectively (see figure 8.2).

intermediate, which is a local minimum on the energy surface,

was set to zero in figure 8.2

The potential energy surface shows that there exists a

narrow channel, through which the bound methyl radical can rotate around the

hydroxo hydrogen to bind with the oxygen. The channel is very flat up to an

H-O-C angle of about 60 degrees, with a small maximum at an angle of

30 degrees (transition state no.2), but then enters a very steep well

associated with the irreversible formation of methanol. From the

zero-Kelvin energy, this second step seems thus much more likely than

formation of the free methyl radical.

However, if we include zero-point energy effects, temperature corrections

and entropy effects, we see that the free energy barriers are similar,

namely 5.2 and 5.3 kcal/mol, respectively (see figure 8.2).

This rebound mechanism has also been theoretically predicted to be the

reaction mechanism for the methane-to-methanol oxidation by the enzymes

P450 and MMO (as aforementioned in the introduction).

In these complexes, a Fe![]() O

species is ligated by either a porphyrin ring via four nitrogens (P450) or

octahedrally by none-heme ligands via connecting oxygens (MMO), which makes especially

the latter interesting to compare our results with. Literature

values for the energetics are compiled along with our results in

table 8.3. We see that also in these biological

complexes the methane is initially very weakly bound in the reactant complex

and that the overall formation of the product complex is very exothermic.

The reaction barriers in between, however, are significantly higher for the

oxidation by the enzymes than by the aqua ligated iron oxo species. For methane

oxidation by P450,

Ogliaro et al. found a barrier of 26.7 kcal/mol for the hydroxylation,

and 29.1 kcal/mol for the rebound step, although the latter barrier vanishes

if the system is allowed to cross to the low-spin surface[160].

Cytochrome P450 is known to be incapable of oxidizing methane, in contrast

to MMO. Still, Basch et al find a barrier for H-abstraction by MMO which is

almost as high as the one for P450, equal to 23.2 kcal/mol[186].

Siegbahn found a much lower barrier with MMO, namely 13.8 kcal/mol, which is still

11 kcal/mol higher than the barrier we find for the oxidation with aqua iron

oxo[185]. The cited work on P450 and MMO was performed using the hybrid

B3LYP functional, which is known to sometimes give better transition state energies

in cases where these barriers are underestimated by GGA functionals, see for

example ref. bernd2.

However, a comparison of these two functionals for the hydroxylation of H

O

species is ligated by either a porphyrin ring via four nitrogens (P450) or

octahedrally by none-heme ligands via connecting oxygens (MMO), which makes especially

the latter interesting to compare our results with. Literature

values for the energetics are compiled along with our results in

table 8.3. We see that also in these biological

complexes the methane is initially very weakly bound in the reactant complex

and that the overall formation of the product complex is very exothermic.

The reaction barriers in between, however, are significantly higher for the

oxidation by the enzymes than by the aqua ligated iron oxo species. For methane

oxidation by P450,

Ogliaro et al. found a barrier of 26.7 kcal/mol for the hydroxylation,

and 29.1 kcal/mol for the rebound step, although the latter barrier vanishes

if the system is allowed to cross to the low-spin surface[160].

Cytochrome P450 is known to be incapable of oxidizing methane, in contrast

to MMO. Still, Basch et al find a barrier for H-abstraction by MMO which is

almost as high as the one for P450, equal to 23.2 kcal/mol[186].

Siegbahn found a much lower barrier with MMO, namely 13.8 kcal/mol, which is still

11 kcal/mol higher than the barrier we find for the oxidation with aqua iron

oxo[185]. The cited work on P450 and MMO was performed using the hybrid

B3LYP functional, which is known to sometimes give better transition state energies

in cases where these barriers are underestimated by GGA functionals, see for

example ref. bernd2.

However, a comparison of these two functionals for the hydroxylation of H![]() by a bare iron oxo species showed that there is good agreement on the

reaction barriers among the B3LYP and BP86 functionals, although the overall

reaction exothermicy was found to be 10 kcal/mol smaller by the BP86 functional

compared to the B3LYP functional[168]. Since discrepancies between the

functionals

are typically amplified in such small bare atom reactions, we expect

much smaller discrepancies between energetics calculated with B3LYP and BP86 for

the present complexes.

by a bare iron oxo species showed that there is good agreement on the

reaction barriers among the B3LYP and BP86 functionals, although the overall

reaction exothermicy was found to be 10 kcal/mol smaller by the BP86 functional

compared to the B3LYP functional[168]. Since discrepancies between the

functionals

are typically amplified in such small bare atom reactions, we expect

much smaller discrepancies between energetics calculated with B3LYP and BP86 for

the present complexes.

The O-H and C-H distances in the first transition state (i.e. the one

for the hydroxylation step) (see

table 8.4) are very similar to those found for the

biochemical hydroxylations. For MMO, Siegbahn found ![]() =1.24 Å

and

=1.24 Å

and ![]() =1.30 Å, and Basch et al found

=1.30 Å, and Basch et al found ![]() =1.21 Å

and

=1.21 Å

and ![]() =1.33 Å, which compares well with

the ones in our transition state (

=1.33 Å, which compares well with

the ones in our transition state (![]() =1.20 Å and

=1.20 Å and

![]() =1.34 Å). For the P450 transition state, Ogliaro et al found

=1.34 Å). For the P450 transition state, Ogliaro et al found

![]() =1.09 Å and

=1.09 Å and ![]() =1.50 Å, which lies relatively

closer to the Fe

=1.50 Å, which lies relatively

closer to the Fe![]() -OH

-OH![]() CH

CH![]() intermediate state.

Summarizing, we find that, apart from the higher barrier for hydroxylation

in the MMO case, the rebound mechanism for methane-to-methanol oxidation

by the pentaaqua iron(IV)oxo species is quite similar to the mechanism

for the methane oxidation by MMO, calculated by Siegbahn. The hydrated ferryl ion

in vacuo is found to be a highly reactive species, very well capable of

hydroxylation and oxidation reactions with an organic substrate.

intermediate state.

Summarizing, we find that, apart from the higher barrier for hydroxylation

in the MMO case, the rebound mechanism for methane-to-methanol oxidation

by the pentaaqua iron(IV)oxo species is quite similar to the mechanism

for the methane oxidation by MMO, calculated by Siegbahn. The hydrated ferryl ion

in vacuo is found to be a highly reactive species, very well capable of

hydroxylation and oxidation reactions with an organic substrate.